SEAMLESS

By Thomas Connors

PHOTOGRAPHY ©CRISTÓBAL BALENCIAGA MUSEUM, GETARIA, SPAIN

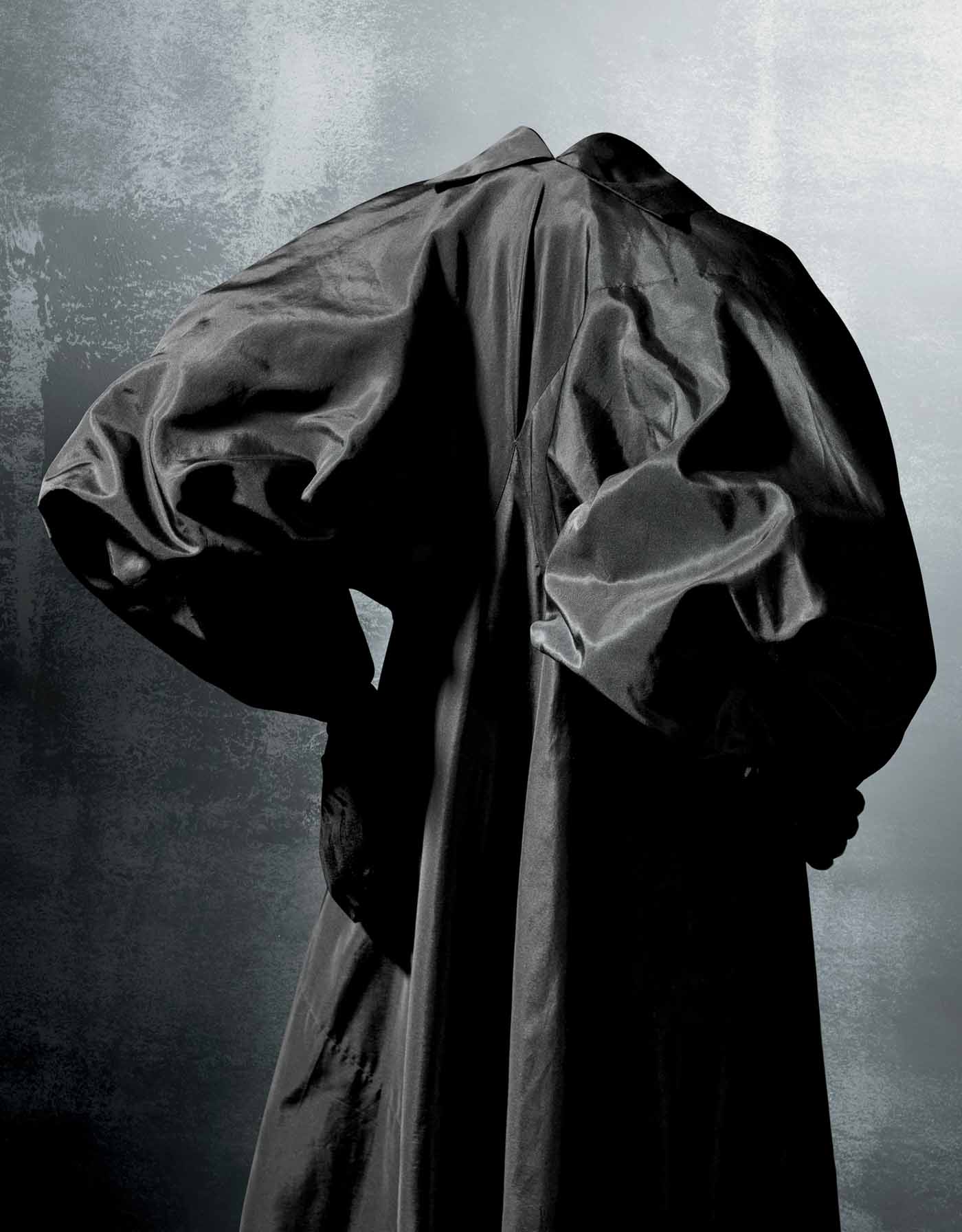

Balenciaga orange wool crepe day dress 1968

By Thomas Connors

PHOTOGRAPHY ©CRISTÓBAL BALENCIAGA MUSEUM, GETARIA, SPAIN

Balenciaga orange wool crepe day dress 1968

For all the audacity of The Met Gala, for all the glitz and glamor of the red carpet, to a fashion fan with a taste for history, there’s something almost magical about the days when “House of ” telegraphed a kind of gravitas, and a salon was a sanctum where women of means, more than celebrity, went to replenish their closets. While the world of haute couture endures, the democratization of fashion, the acceptance of street style, and the readiness to mix a luxury outfit with a Target accessory makes one appreciate even more that golden age when couturiers—like Cristóbal Balenciaga—were a special breed indeed.

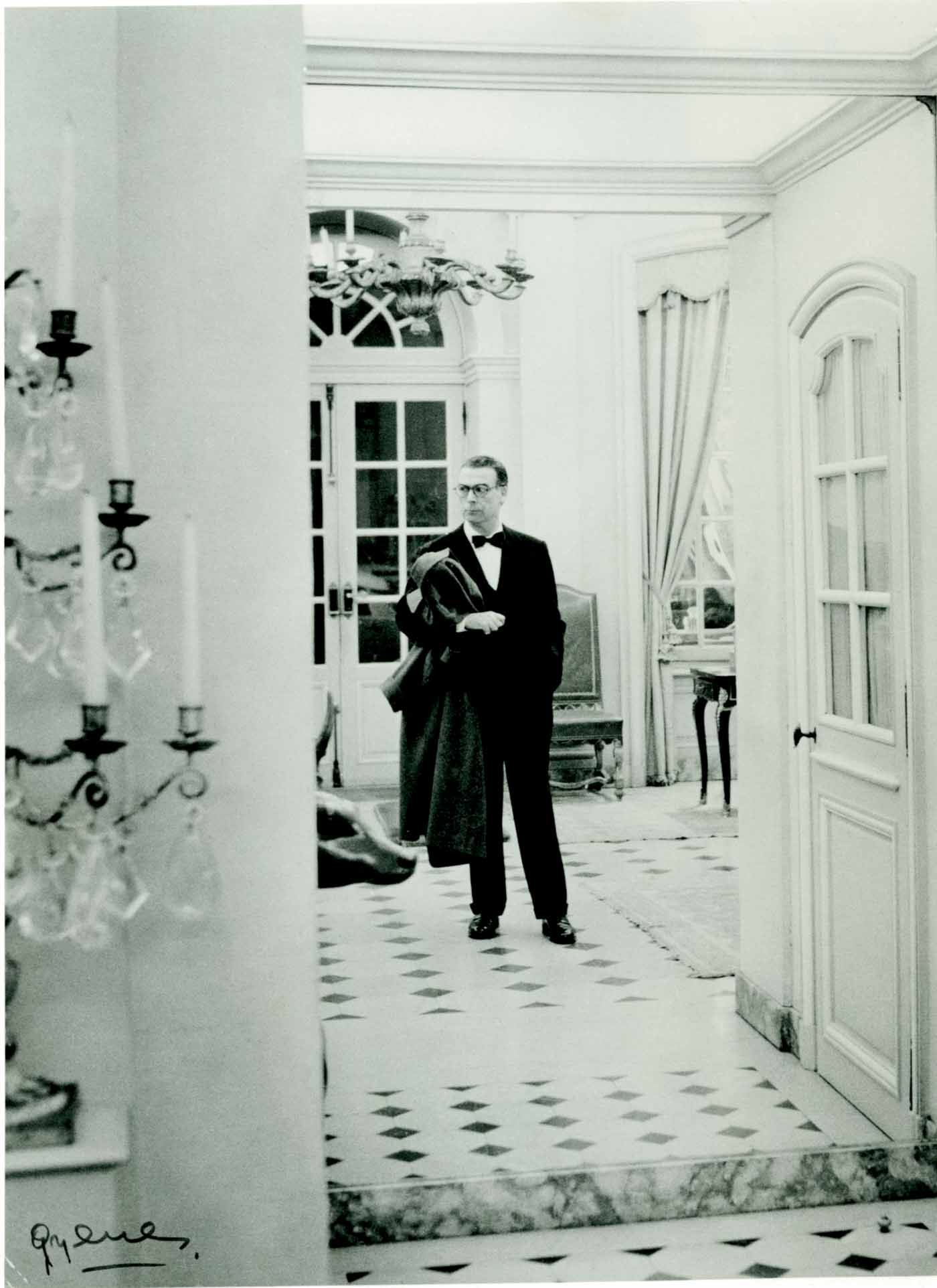

The son of a fisherman and a seamstress born in 1895, in Getaria, Spain, a village in the Basque country, Balenciaga took to needle and thread early on. At 12, he was apprenticed to a tailor in nearby San Sebastián, where Spain’s Queen Maria Cristina had spent her summers. A decade later, he opened his first boutique and within a few years, employed dozens of people. With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, he relocated to Paris, dreaming of giving Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli a run for their money.

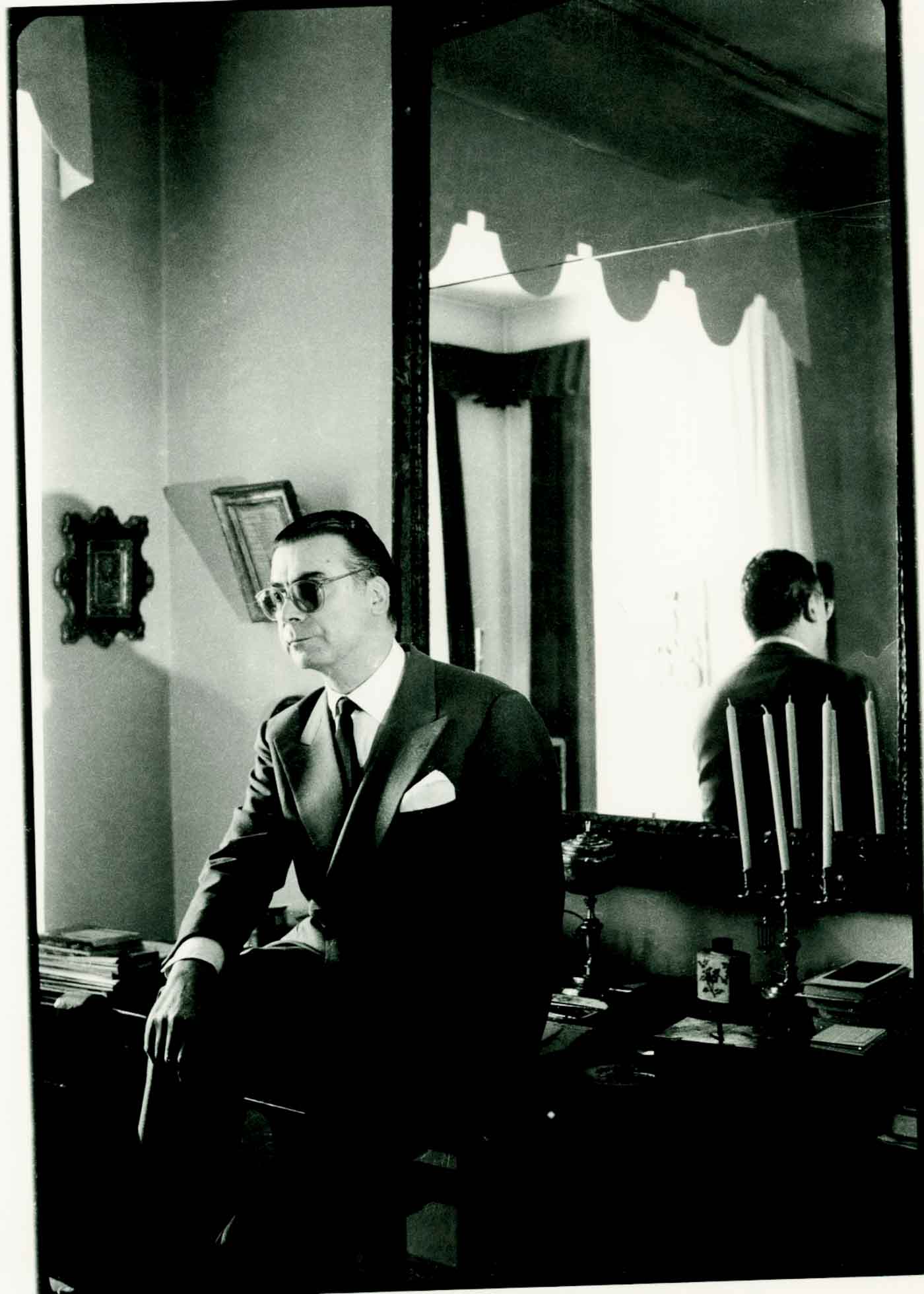

Balenciaga—whose life has been captured in a Spanish-made mini-series that aired on Disney+ this year—was over 40 when he opened a boutique at 10 Avenue George V. His creations, which often referenced the line and profile of garments worn by Spanish women, were something fresh and new in the City of Light and the designer soon garnered admirers. Always fastidiously crafted, his clothes became more visually dramatic and were by turns, voluminous and flowing and crisp and geometric.

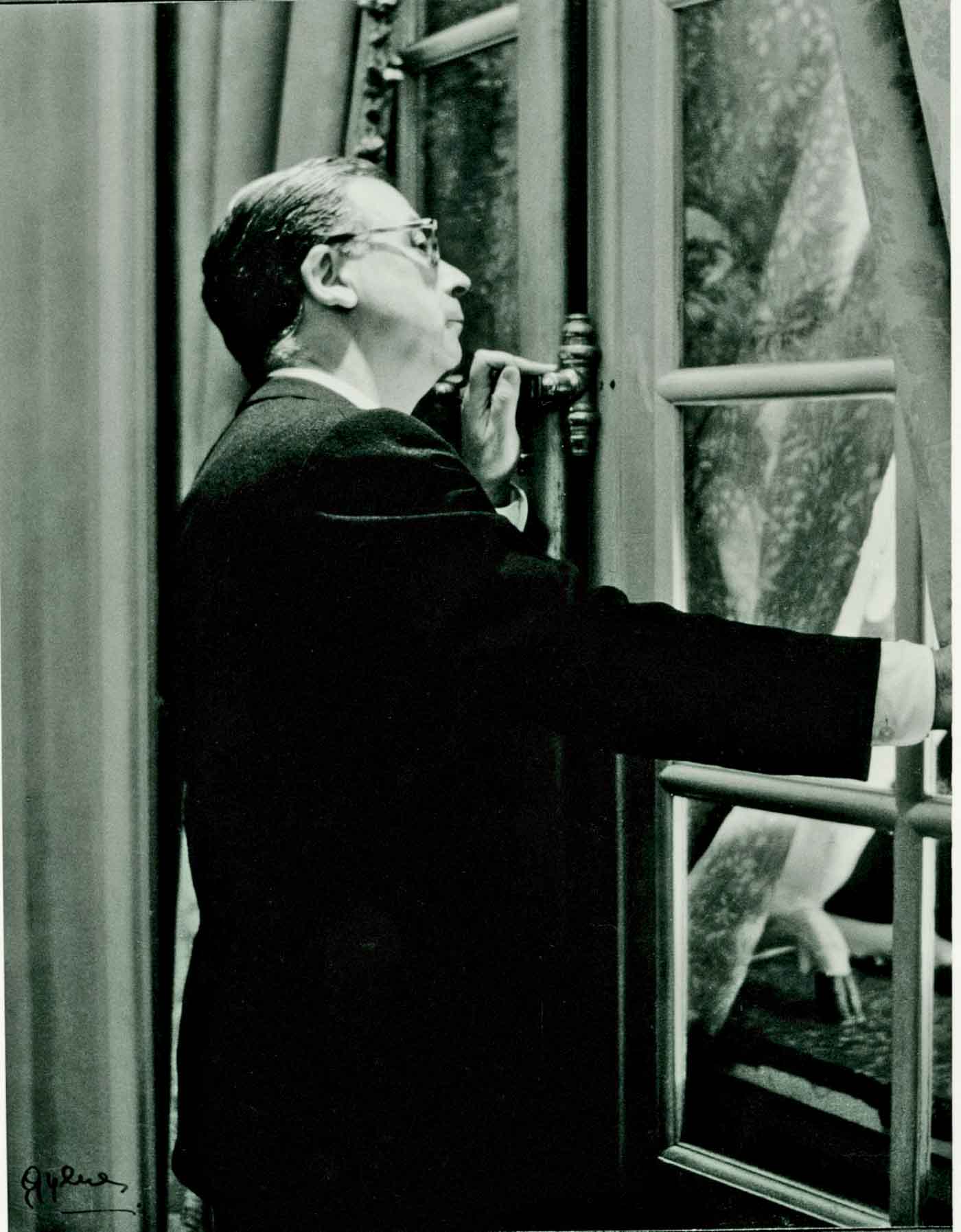

When Christian Dior introduced his “New Look” in 1947— which challenged the leftover fripperies of the ‘20s, the dourness of the ‘30s, and cast off the financial and material constraints of the war years—fashion entered a truly glorious period of exuberant experimentation with Balenciaga standing at the forefront of this brave new world. Although it was the final product that captivated fashion editors and customers, his peers’ appreciation began with what transpired in the workroom. In a 1951 issue of Paris Match, Coco Chanel asserted, “The others are draftsmen or copyists, or else they are inspired people or even geniuses, but Balenciaga alone is a couturier. He is the only one who can design, cut, put together, and sew a suit or a gown entirely alone.”

Aloof and publicity averse (photographer Cecil Beaton opined, “Balenciaga stands apart, like some Elizabethan malcontent meditating upon the foibles and follies of fashion”), the designer nonetheless moved with the times, finding new ways to adorn the female form in a changing world. Simple, but formidably constructed, his work was fundamentally modern. In the 1950s, he detoured from garments that emphasized an hourglass shape, offering up the sack dress (a waistless shift that was gathered below the knee) and the flared, bouncy baby doll dress—a playful, somewhat naughty design that wouldn’t be out of place in a painting by Balthus. When the ‘60s rolled around, Balenciaga fully expressed the era’s energy in such pieces as a streamlined day dress done in florescent orange crepe with deep-cut armholes revealing essentially another dress underneath.

In 1968, with ready-to-wear on the rise, Balenciaga retired. Although a German pharmaceutical interest bought the house, it did little more than produce perfume until the 1980s, when a series of designers came on board to revive the brand, including Nicolas Ghesquière, who made the name shine again. In recent years, Balenciaga has been known for provocative designs and dubious marketing. In 2022, an ad featuring children holding stuffed toys in bondage gear seemed about to deep-six the company. But it survived. This summer, Balenciaga opened its first free-standing store in Chicago, at 15 East Oak Street.

It’s arguable whether the house’s current offerings honor the spirit of its founder, who died in 1972, but Balenciaga has its fans, including Kim Kardashian. Fashion changes, of course, and one woman’s must-have is another’s “no thanks.” But as the Cristóbal Balenciaga Museum in Getaria attests, nothing can diminish the designer’s achievements. In gallery after gallery, one encounters the full range of the designer’s work, artfully framed in minimalist vitrines. Evidence of the master’s conviction that “a couturier must be an architect for plans, a sculptor for shapes, an artist for color, a musician for harmony, and a philosopher for the sense of proportion,” these singular creations stand for something more: a belief in fashion as almost a moral responsibility.

For more information, visit cristobalbalenciagamuseoa.com.

Sign Up for the JWC Media Email