RESPLENDENT GRIT

By Eileen G'Sell

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JAMES GUSTIN

STYLING BY THERESA DEMARIA

HAIR & MAKEUP BY MARGARETA KOMLENAC

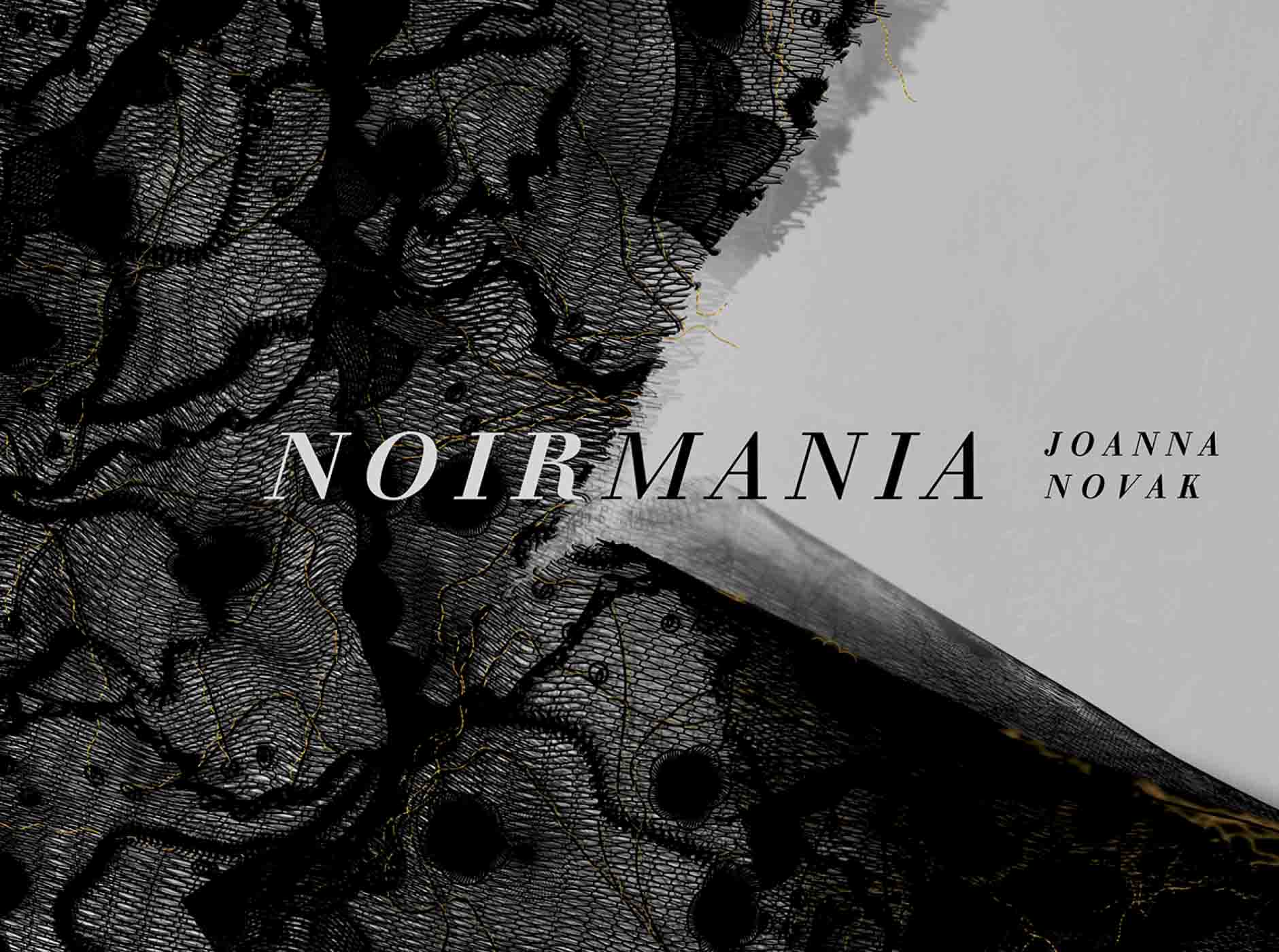

JoAnna Novak wearing Zimmermann and photographed with her dog Lucy.

By Eileen G'Sell

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JAMES GUSTIN

STYLING BY THERESA DEMARIA

HAIR & MAKEUP BY MARGARETA KOMLENAC

JoAnna Novak wearing Zimmermann and photographed with her dog Lucy.

It’s a brisk, sun-blanched morning, and I’m walking from River North to the Ukrainian Village to check out Kasama, the Michelin-starred Filipino joint recently featured on Hulu’s The Bear. On the way, I pass Augusta and Paulina’s Auto Repair and indulge in the fantasy that the spot is run by two female mechanics—complicated, scrappy women who look great in coveralls and are unafraid to get their hands dirty.

Such a premise would well suit a story by JoAnna Novak—be it short fiction (her collection Meaningful Work came out in 2021) or a novel (her debut, I Must Have You, was released in 2017). Novak’s narratives are packed with unexpected female protagonists as difficult as they are daring. To call them “heroines” feels imprecise; Novak doesn’t attempt to morally justify, let alone heroize, her characters’ motives or actions. She instead lets them fret, rage, second-guess, manipulate, and stew. Novak doesn’t just allow women a full range of emotions, savory or not, she celebrates their capacity to implode yet survive, to crash into the highway medians of life, only to exit via hatchback and hitch a ride out of state.

I’m meeting Novak in the Kasama brunch line because we share a penchant for imaginative pastries and extravagant people-watching. I’ve known the author and poet for 13 years, and have dined with her in Brooklyn, Albany, New Haven, Kansas City, and Los Angeles. But this is the first time we’ve broken bread (or, in this case, black truffle croissants) in her hometown.

After two decades away—pursuing a Bachelor of Arts at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, a Master of Fine Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, another in Amherst, Massachusetts, and a forthcoming Ph.D. at the University of Southern California— Novak has returned to the Windy City with her husband, 3-year-old son, and feisty Chihuahua Papillon mix. Making a home in Evanston, Novak approaches this new chapter with characteristic curiosity. “Evanston, and all of the North Shore, really, is so rich with mystery and natural beauty,” she tells me. “I get ideas when I’m running along Lake Michigan, especially when the waves rival those on Venice Beach.”

Novak’s most recent book, her first memoir, is called Contradiction Days, inspired in part by the author’s obsession with abstract painter Agnes Martin, who fled the New York art scene in 1967, packing up her art studio, giving away her materials, and disappearing in a pickup truck only to resurface in Taos, New Mexico 18 months later. In title alone, Contradiction Days speaks to the complexity of both Martin and its paradoxical narrator. Now 38, Novak is a quiet person with a provocative mind, a fashion maven who frequents public libraries, a culture vulture entirely absent from social media. Her refulgent condo—housed in a former Nabisco factory—radiates an airy buoyancy at odds with the darker impulses of her writing. It’s also a 180 from the sage-brushed desert topography of Taos, where Novak took her family in 2019 four months before her son was born to embrace a “life of renunciation.” And also, of course, to write a book.

Like any Novakian literary venture, Contradiction Days is no beachside read. Novak is not a beachy person (don’t let the Chanel espadrilles fool you). Chronicling the author’s brutal experience of perinatal depression, the memoir is a beautiful, disquieting account of toggling between the demands of a creative life and those of literally creating life as a mother. “It was hard enough to be a human being,” the narrator reflects, “… but hardest of all becoming a mother when you’re a woman human being whose reproductive urges have been satisfied by her art.”

And how did she push through it—reaching for the “positive freedom” that the artist-mystic Martin espoused? With typical Midwestern grit. “Discipline was an expectation and a virtue in my home,” she explains. “Being ‘off the streets and out of trouble,’ as my grandmother liked to joke, was a pathway to imperviousness. Of course, imperviousness is sort of overrated, but I had to learn that the hard way.”

These days, life remains contradictory, but on the whole feels much more tranquil. Every morning, Hewn Bakery beckons Novak from a few blocks over. Her son is enrolled in pre-K at the same school where her husband teaches English. “My office looks out onto treetops and train tracks,” she describes. “In the mornings, it seems like there’s nothing but sky.”

For more information, visit joannanovak.com.

Sign Up for the JWC Media Email