PAINTING WITH VALUES

By Monica Kass Rogers

WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY MONICA KASS ROGERS

STYLING BY THERESA DEMARIA

Hector Hernandez wearing Theory pant, Zegna shirt, Brunello Cucinelli sweater

By Monica Kass Rogers

WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY MONICA KASS ROGERS

STYLING BY THERESA DEMARIA

Hector Hernandez wearing Theory pant, Zegna shirt, Brunello Cucinelli sweater

At 10:30 a.m.the light filtering through the windows in Lake Forest is beautiful. “Yes,” artist Hector Hernandez says, smiling appreciatively, “David Adler designed this estate so that every room is perfectly lit by natural light. It’s so helpful when I paint.”

One of few artists still working in technique mixte, the 15th-century painting technique that made works by Da Vinci, Raphael, and other Renaissance painters so glowingly beautiful, Hernandez uses a mixture of egg tempera and oil to create his painting’s underlayers first, allowing each to dry for days. “This indirect method of painting is like creating a foundation for a house before you start building on top of it,” Hernandez explains. “With technique mixte, we paint with values (lights and darks) first, and then on top of those we apply color in very thin coats so that light penetrates each color and bounces back, illuminating the work.”

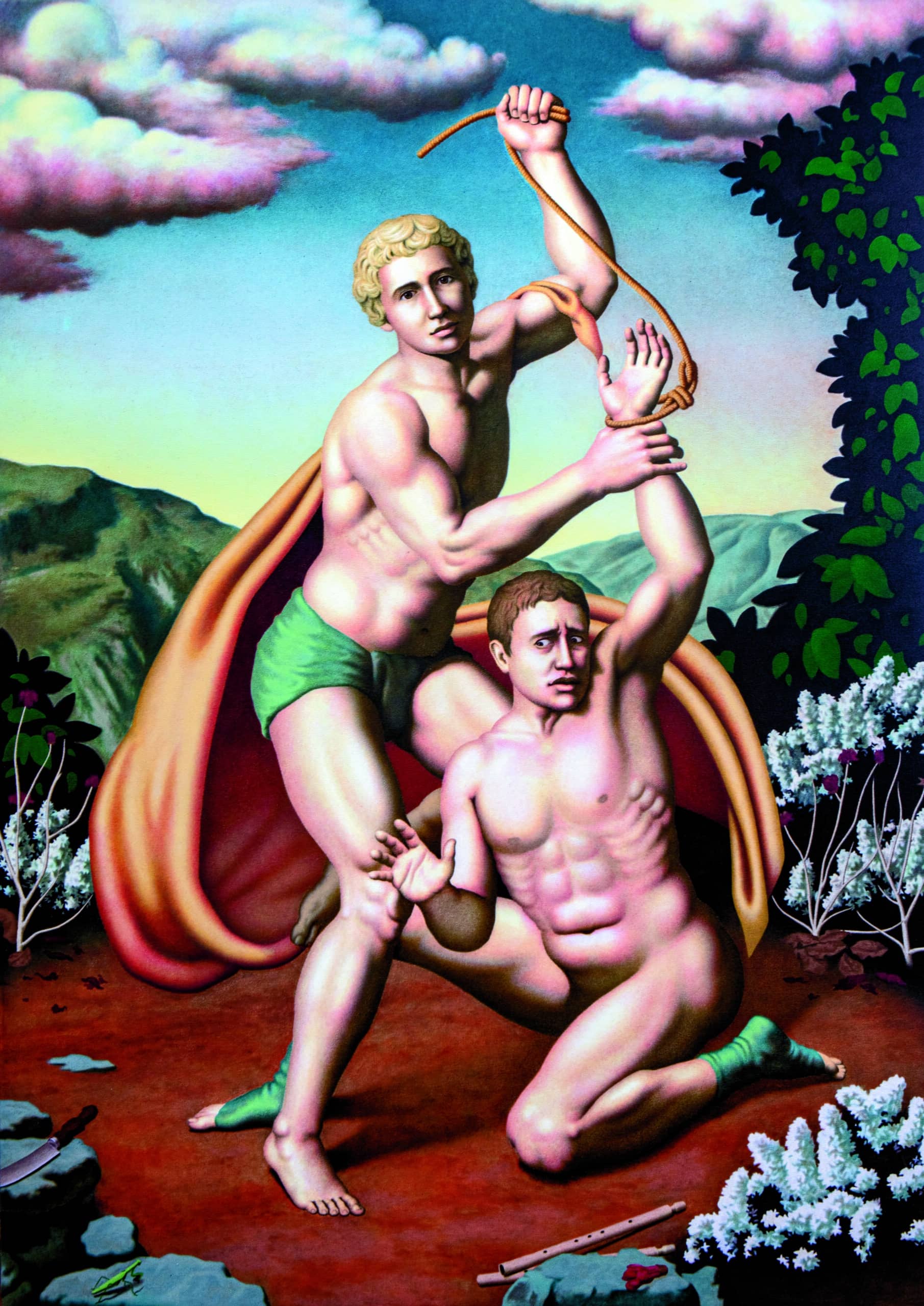

Upstairs, Hernandez leads the way to the studio where he is putting the finishing touches on a vibrantly rich, life-sized painting depicting the cautionary tale of Apollo and Marsyas. In the story, the satyr Marsyas, famous for expertly playing an oboe the goddess Athena had tossed down to earth, became so prideful about his musicianship that he challenged Apollo to a musical contest. Apollo wins, of course, and exacts harsh punishment on the satyr for his hubris. “It’s the classic pride comes before a fall story,” says Hernandez, who has painted the figures in an epic wrestling match.

While technique mixte is laborious, difficult, and time-consuming, Hernandez believes this painting method transcends others. The first paintings he saw created this way were by Patrick Betaudier, a technique mixte master and founder of The Atelier Neo Medicis in Montflanquin, France. “I was blown away when I saw Patrick’s work,” Hernandez recalls.

Just out of high school and a student at The American Academy of Art, Hernandez spent five years studying with Betaudier in France and the United States during summer breaks from school.

Once he gained some mastery of the technique, Hernandez set off on a personal quest. Born in Mexico to a family that immigrated to Chicago when he was very young, Hernandez heard important stories about his ancestor’s lives in Mexico but wanted to know more. “I wanted to connect with my family’s roots,” Hernandez explains. “My great-grandfather and other relatives were among the thousands who lost their lives in the Cristero War in the 1920s, a rebellion set off by the government’s persecution of Roman Catholics and a ban on their public religious practices,” says Hernandez. “Because of this persecution, my family held more tightly to their faith rather than rejecting it and that shaped my own value system and ultimately, my interest in art.”

What was intended to be a six-month sojourn to Jalisco, Mexico, turned into an 11-year stay, during which Hernandez painted works commissioned by individual clients and the church.

“Things just opened up before me,” says Hernandez. “Understanding more about my family’s experience encouraged me to go down the path of traditional painting I have taken.”

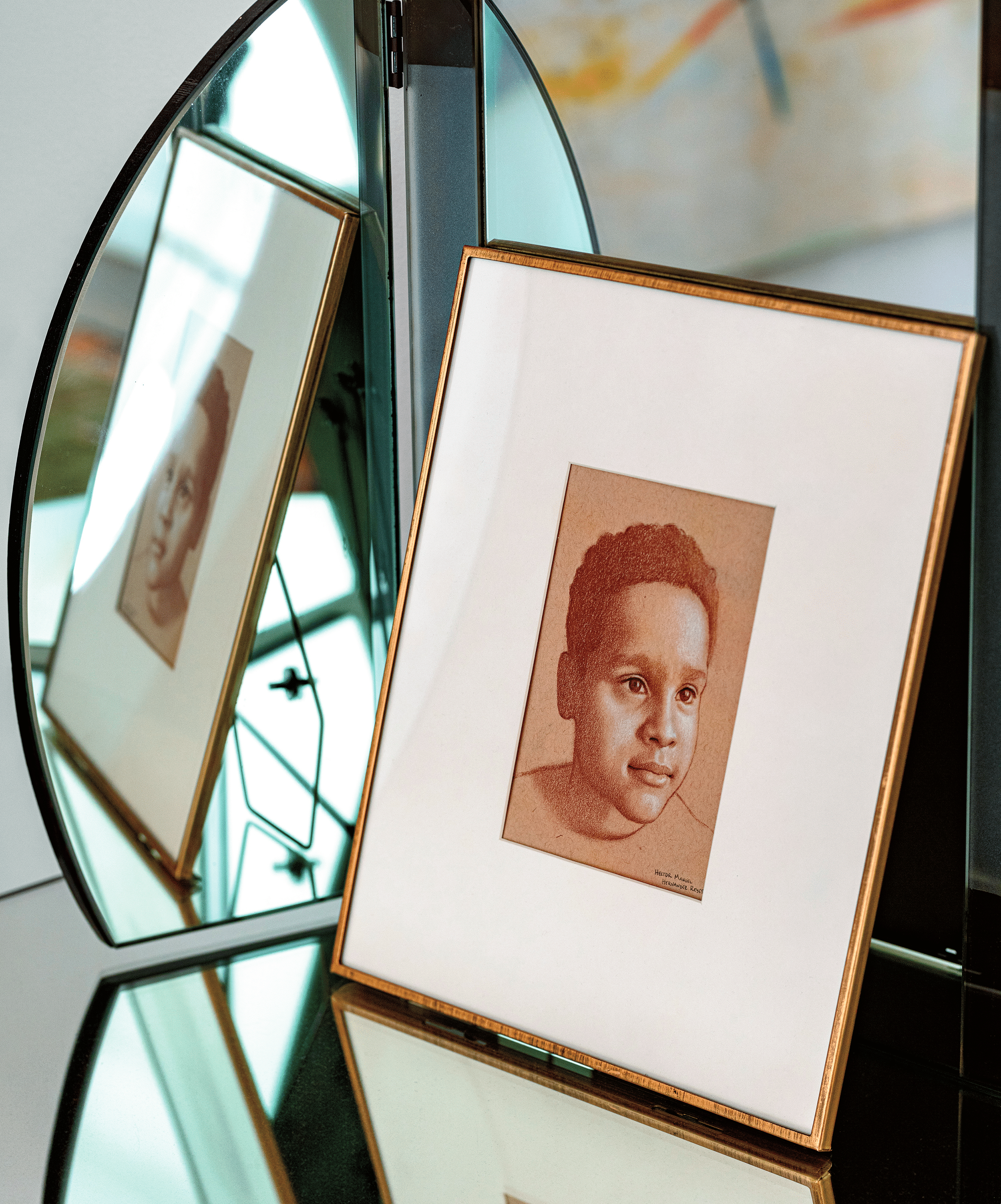

Now permanently back in the States and serving as a resident artist, Hernandez is busy both painting and teaching. All of his work is by commission. In particular, he loves painting portraits because they allow him to “capture the essence of a person’s soul at a fixed moment in time.” Hernandez also paints allegorical and religious works for clients here and in Mexico.

Like the painting of Apollo and Marsyas in his studio, his work is often inspired by stories with universal meaning. “There are so many stories that resonate universally—stories rich in innate values, concepts, and metaphysical necessities that go beyond the material to touch who we are as human beings. Those are the stories I want to use as subject matter.”

Hernandez’s painting of St. Sebastian, for example. A Roman soldier who was also a Christian, Sebastian was martyred for his beliefs in a story eerily similar to that of Hernandez’s ancestors.

“It’s true,” Hernandez smiles wistfully. “St. Sebastian became a symbol of righteous rebellion in the same way that my great-grandfather and others in the Cristero War were. But I think all memorable art takes us to the larger questions. I seek to be a painter who tries to capture these bigger truths because I believe that is part of art’s role in society. Ultimately, I’m searching for the good. Values, concepts, and ideas that have existed throughout history. I want to preserve these things in my work.”

To commission artworks from Hector Hernandez or to take oil painting classes at the studio (offered from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. and 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. on Mondays and Wednesdays), email [email protected] or call (224) 507-2270.

Sign Up for the JWC Media Email