Long And Winding Road

By Adrienne Fawcett

By Adrienne Fawcett

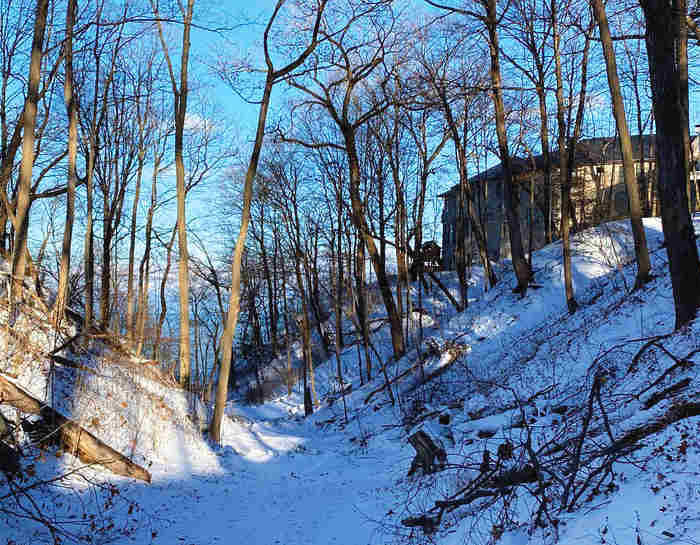

THERE’S A 16-FOOT-WIDE path in a Lake Bluff ravine that’s been called Lillian Dell’s Drive for a long time.

But just who was Lillian? This important detail was forgotten until recently, when Lake Bluff History Museum pieced the story together.

Today Lillian Dell’s Drive has colorful new signs courtesy of the Village of Lake Bluff. The ravine also has a rocky history. It played a pivotal role in the lives of Native Americans, pioneers, summer guests and year-round villagers, and it even wound up on the Illinois Supreme Court docket. The ravine also has been a surreptitious toboggan run for generations.

Long ago, Native Americans traveled to the ravine to harvest flint, according to oral history preserved by the Museum. In 1836, the area’s first European settlers, immigrants John and Catherine Cloes, laid claim to 100 acres of land, including the ravine.

Methodist businessman Solomon Thatcher was charmed by ravines when he founded the Lake Bluff Camp Meeting Association in 1875. The summer resort transformed the ravine into a drive for horse-drawn carriages. By night, summering couples strolled the secluded path to the lake, earning the drive the moniker, “Lover’s Lane.”

But who was Lillian?

Lillian Dell Friestedt’s family summered in Lake Bluff in the late 19th century. She and twin brother George were born in 1885 to Luther Peter and Dorothea Heuer Friestedt. Sadly, Lillian died in 1887, according to Lynn Friestedt Steffen, a longtime Lake Bluff resident whose great-grandparents were Luther and Dora.

In 1901, Luther purchased land straddling the ravine. In 1909 he subdivided it and donated the ravine path in memory of his daughter Lillian Dell “as a public driveway to be kept in repair by the Village of Lake Bluff and to be used and maintained for a pleasure driveway only.”

Drama around Lillian Dell’s Drive started in 1916, when the Village became embroiled in a lawsuit with new owner John Crosby, who built a fence across the ravine and posted signs claiming ownership. Another lawsuit, in 1950, placed Lillian Dell’s Drive before the Illinois Supreme Court when homeowners challenged the Village’s maintenance and questioned whether the drive should allow automobiles. The court sided with the Village, saying no to cars.

What would Dora and Luther have thought of the tug of war over their daughter’s memorial drive? With their deaths in 1913 and 1917, respectively, the family’s connection to Lake Bluff was lost, but not forever. In the 1950s, the couple’s grandson Frederick Friestedt moved to Lake Forest with his wife, Blanche, a real estate broker. No one mentioned that an earlier generation had summered in Lake Bluff, according to Lynn Steffen, their daughter.

But one day in 1970, Blanche’s co-worker sold a house in the “Friestedt plat.” Blanche investigated and learned of the family’s long-ago ties to Lake Bluff.

Lynn raised her children, Mark and Erik Steffen, in the Village, and she now lives in Green Oaks with sister, Christine; brother, Bradford, lives in Lake Bluff.

They are thrilled with the new signs at Lillian Dell’s Drive, a path named for their ancestor, a little girl whose connection to Lake Bluff was forgotten for decades. And is now remembered.

Sign Up for the JWC Media Email