HEAD IN THE GAME

By Joe Rosenthal

PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF THE CONCUSSION LEGACY FOUNDATION

Chris Nowinski, co-founder of the Concussion Legacy Foundation

By Joe Rosenthal

PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF THE CONCUSSION LEGACY FOUNDATION

Chris Nowinski, co-founder of the Concussion Legacy Foundation

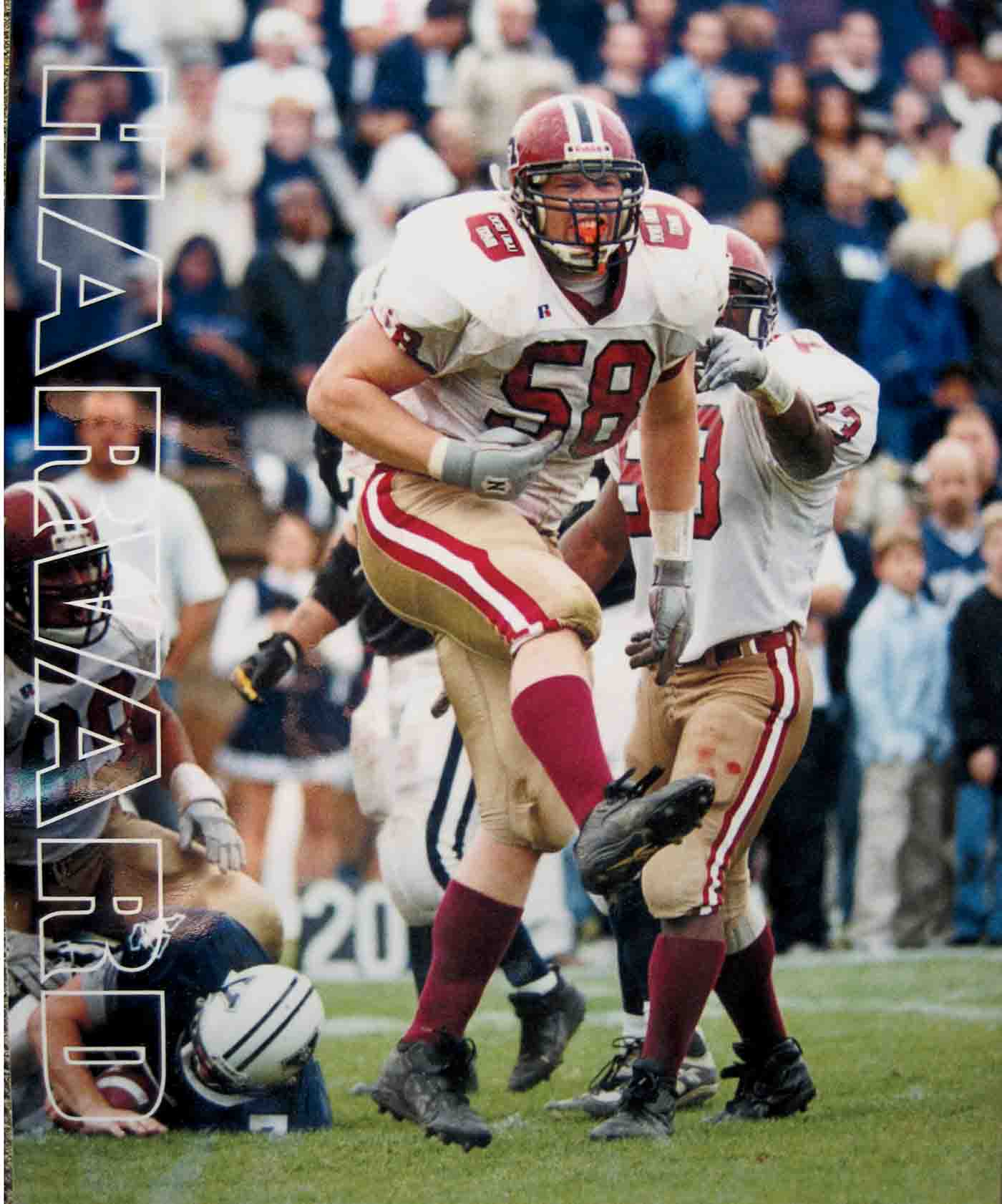

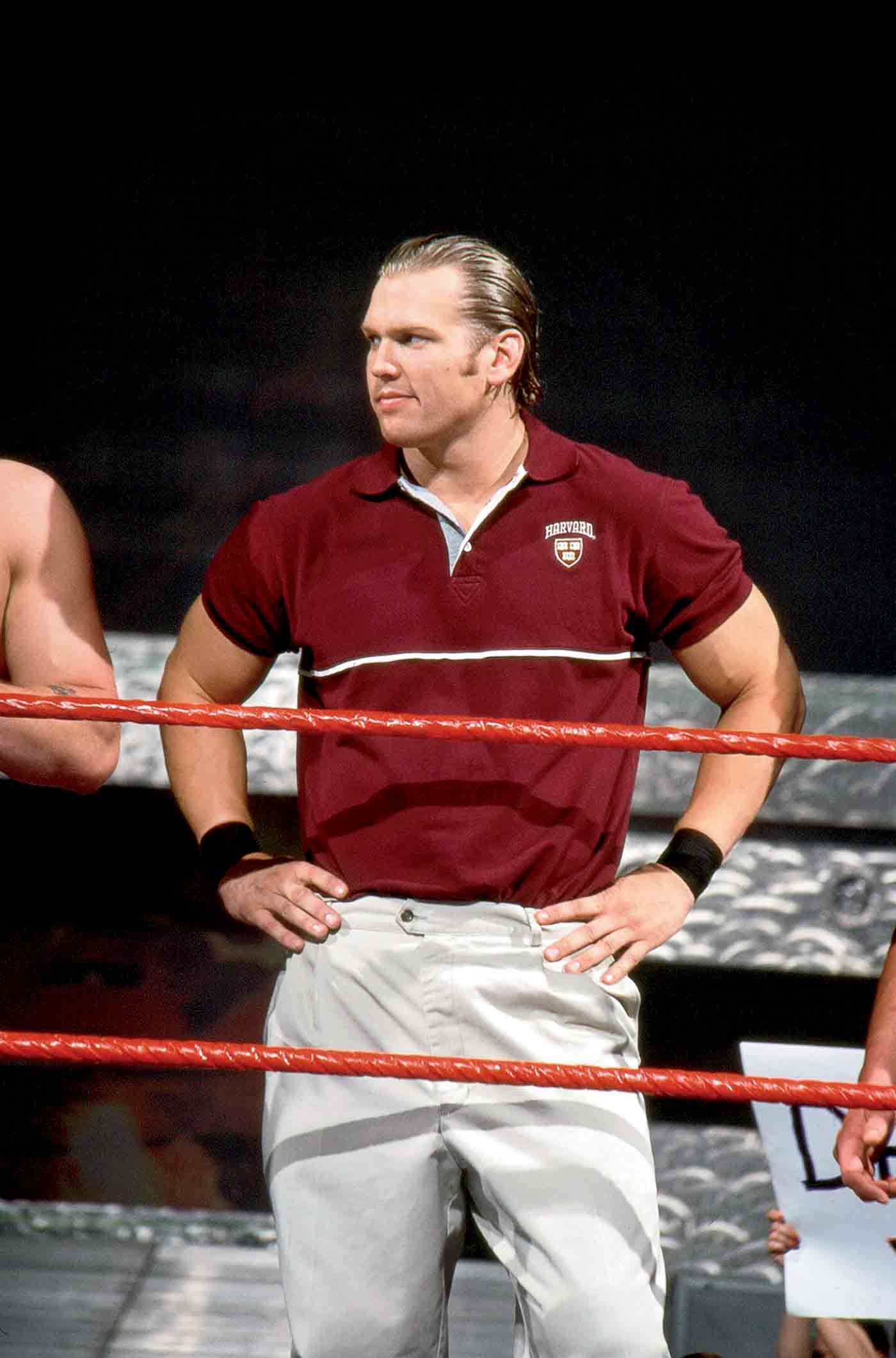

Chris Nowinski isn’t a person who scares easily. He was a standout football player at John Hersey High School in Arlington Heights and took his gridiron skills to college, where he played defensive tackle for Harvard and won All-Ivy honors. As Chris Harvard in the WWE, he didn’t bat an eye before jumping into the wrestling ring, flying off ropes, and dodging (most of the time) chairs being swung at him.

But these days Nowinski finds himself preoccupied by worries that jar him as much as the hits he took over so many years. He’s afraid about how often our kids are getting hit in the head while playing the sports that had meant so much to him in his youth. He fears what will happen to these kids, their families, and their friends if we don’t accelerate research efforts and change how we play sports.

After being sidelined from his WWE career by a serious concussion in 2003, Nowinski became an advocate for concussion awareness and prevention. He earned his doctorate in behavioral neuroscience and co-founded the Concussion Legacy Foundation with Dr. Robert Cantu to promote safer sports and safer athletes and an end to chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease linked to repeated head impacts (CTE). The nonprofit organization collaborates with the Boston University CTE Center in research, and together with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs they founded the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, the preeminent CTE resource in the world.

Sheridan Road caught up with Nowinski late last fall, just days before the publication of a report documenting the first case of a teenage football player diagnosed with advanced CTE. The 18-year-old from Missouri, who began playing tackle football in third grade, exhibited stage 2 of CTE’s four stages. Before he died by suicide, the young player asked his family to donate his brain to research, and he spoke openly about the concussions he’d suffered in football and how bad they made him feel. Although research didn’t positively correlate the symptoms that led to his death with CTE, research is clear that football can cause CTE.

“We need to recognize that children’s brains are fragile and that there are only so many hits they can take before the risk of a life-altering concussion or developing CTE comes into play,” says Nowinski. He points out that we’re living in an era quite different from the one he experienced 30-plus years ago. Kids are now playing longer seasons, more games, more tournaments, and playing contact sports almost year-round. It is, in some ways, an ongoing experiment simply because this level of play hasn’t happened before.

Nowinski points to the largest CTE study ever, which included over 600 football players. It showed that more than 75 percent of those who played 10 or more years of football had CTE. While the researchers don’t suggest this accurately reflects risk for everyone who played 10 or more years since families donate the brains of loved ones who had neurological symptoms, Nowinski says it is concerning how frequently CTE is diagnosed in this population.

“There’s no excuse in 2024 for kids to be exposed to sports where they get hit in the head hundreds of times a year now that it’s proven that it causes CTE in some of them,” he says.

Of course, sports are popular because we love them—we love playing them, watching them, and it’s fun to see our kids play the sports we loved to play when we were young. It’s a complex issue but according to Nowinski, there is an easy precaution. “The simple advice is don’t let your kid get hit in the head repetitively until they’re at least 14.”

The reasons for the age delay, Nowinski explains, are threefold: “First, the science is extremely clear on cumulative exposure. So, starting later is minimizing the number of years. Number two is brain development. Your brain is going through magical changes when you convert from a child to an adolescent, and head trauma could negatively impact that maturation process. And the third reason is informed consent and your ability to train a child to do anything safely. We know from every aspect of public health that the primary way to prevent a child from getting hurt can’t be asking the child to follow rules, especially as complicated as ramming a moving person or [heading a] moving ball.”

Nowinski speaks positively about how USA Hockey raised the age for body checking and how USA Lacrosse partners with his organization’s Team Up Against Concussions program, which uses a bystander intervention model to deliver a straightforward message to the team: a teammate with a concussion needs your help and should receive immediate medical attention.

“[As a teammate], you may be the only one who sees it,” Nowinski says. “You may be the only one they confess to.” So, the system is put in place for players to help each other from the very start of the season, along with a “team captain” to lead the initiative. It’s about creating the environment for change.

Even with these changes, Nowinski emphasizes that there is still room for improved safety measures. For example, in 2015 his organization successfully advocated to raise the age to head the ball in soccer. To Nowinski’s disappointment, the age was only raised to 11. “There’s just no reason to start at 11,” he argues.

He’s a big advocate of kids only playing flag football before high school. “Flag before 14 is the future,” he says. “You get all the benefits. You just don’t get the mileage on your brain and the mileage on your body.”

Nowinski explains the rationale that supports his viewpoint: “If you don’t play football until 14, and 93 percent of football players will never play after 18, we should be able to make CTE rare in people who play four years of football.”

While there is no known cure for CTE, treatment is available for many symptoms of the disease. The Concussion Legacy Foundation HelpLine is available to provide personalized support for any current or former athletes who are concerned about repetitive head trauma and are looking for help.

“[We can provide] medical referrals, support groups, one-onone support, and education on what they’re going through so that they know that there are thousands of people who’ve been in that situation who’ve gotten better.”

The benefits of youth sports have been well documented for years. Yet, there’s new documentation for the risks as well. Nowinski’s life goal is to keep the scales squarely tilted in favor of the benefits.

Learn more about the Concussion Legacy Foundation or submit a request to the HelpLine at concussionfoundation.org.

Sign Up for the JWC Media Email