CRIME OF THE CENTURY

By Sherry Thomas

By Sherry Thomas

It was around 9 p.m. that fateful June 12, 1924, evening when Doc, Joe, and Jess Newton saw the train roaring up the tracks at Rondout—an unincorporated borough just miles from the edge of Lake Bluff, right off Route 176.

This was it, the moment they’d been waiting for.

The outlaws, Texas natives who were notorious for committing small-time crimes with their brother as part of the Newton gang, had been plotting their biggest heist yet. Working with a few Chicago gangsters and intel from a corrupt postal inspector named William J. Fahy, they staked out the area in black Cadillacs.

Thanks to Fahy’s inside knowhow, the other Newton brother, Willis, was able to sneak on board the train in Chicago with mob-connected criminal Herb Holliday. The plan was to take over the engine car as it approached Rondout, hold up the conductor at gunpoint, and throw formaldehyde into the passenger cars to release debilitating fumes.

Doc, Joe, and Jess were poised and ready to spring into action as it screeched to a halt, jumping on board to force 12 workers off the train. A total of 52 mail pouches containing more than $2 million in cash and jewelry were stolen during the heist, loot that would be worth about $35 million today.

But as Lake Bluff History Museum board member Steve Kraus explains, one fatal flaw would end up taking down the whole operation. Doc Newton had left his post amid the chaos and was mistakenly shot five times by a member of his own gang.

“The Newtons were all in and out of Texas prisons. They were too well known to the Texas Rangers and had to look elsewhere to pursue their criminal career,” says Kraus, who will discuss the heist during the museum’s “Distilling History: The Great Rondout Train Robbery” presentation on June 9, just days before the 100th anniversary of the crime. “They were connected to the fringes of the Chicago underworld, and had the inside connection to try for the big score. Because they were not known to the Chicago cops, the plan may have succeeded, if only Doc hadn’t been in the wrong place.”

The badly wounded Doc Newton had apparently been taken to a flop house on the west side of Chicago while his brothers hid out elsewhere in the city with a few select Chicago gangsters.

“This would have been a very different story if one of the gang had not shot Doc Newton during the robbery. Instead of splitting up and laying low for a planned six months, the gang had to go back into Chicago to find a mob-connected doctor,” Kraus says. “A tipster fingered the house where Doc was resting and four of the gang were in custody the day after the robbery. In exchange for consideration of less jail time, they told the cops where to start looking for the rest of the gang.”

As a result, the Newton brothers never got to split up their booty, which had been stashed in large quantities in a variety of places—one of which, according to Kraus, was the basement of a run-down road house in Wilmette, which “contained $500,000 buried in Mason jars.”

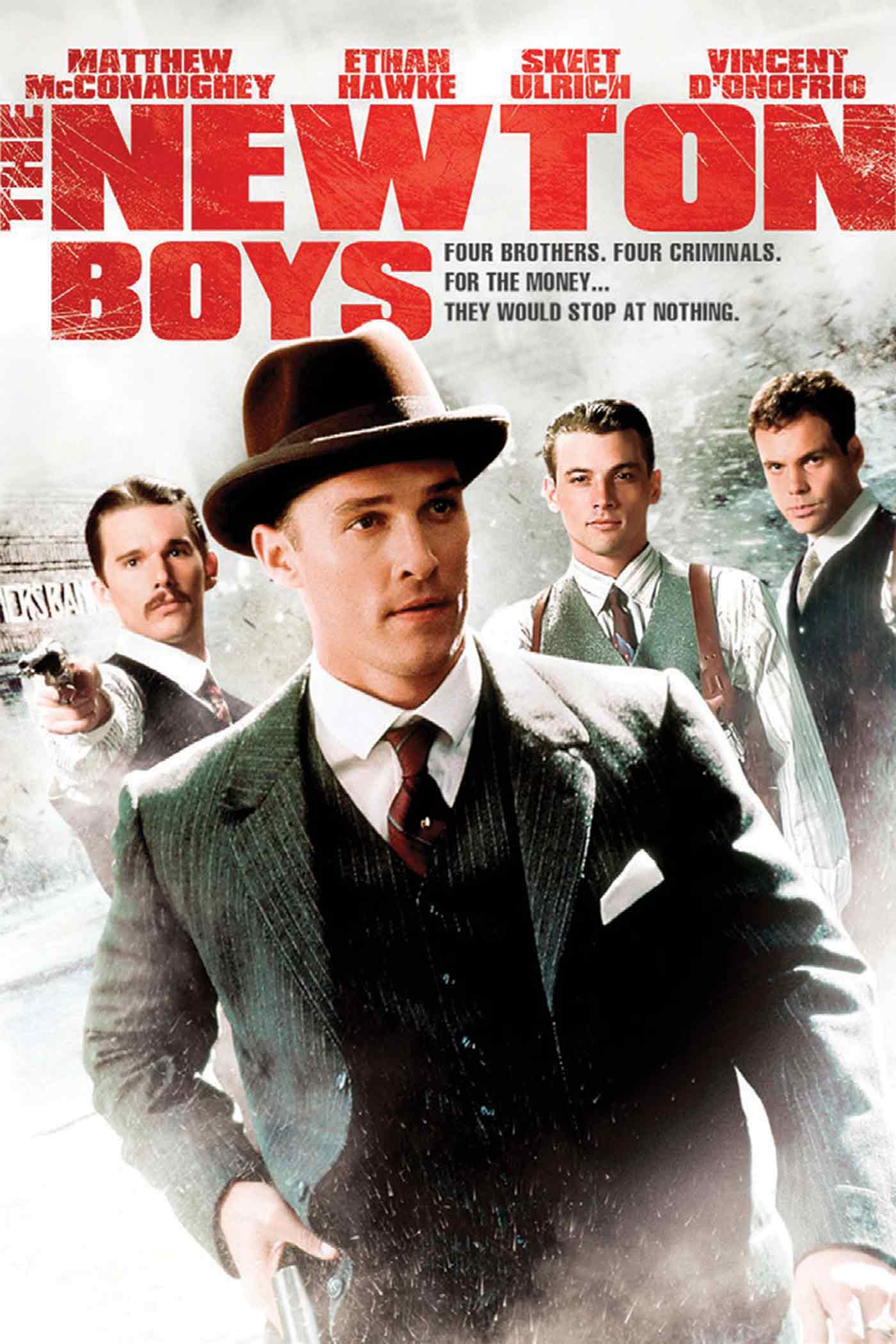

His presentation next weekend at North Shore Distillery in Libertyville (just up the road from the scene of the crime) will delve into the juicy details of what remains the largest train robbery in U.S. history—a crime that made national headlines and was immortalized in books and in Hollywood, including the 1998 film, The Newton Boys starring Matthew McConaughey.

One of the topics Kraus plans to discuss (and take questions about) is about the railroad itself and its importance to early 20th century economy.

“The railroads were the economic lifeblood. In a sense, they were the bankers. Trains carried cash for companies to meet their payrolls and connected people by delivering mail cross country,” he explains. “Trains safely delivered merchandise to homes and businesses, similar to what Amazon does today.”

What’s especially compelling about the Newton brothers tale is how It straddles elements of the old Wild West with modern, 20th century lawmen who were better equipped to stop bad guys. “The Newtons supposedly robbed their first trains while they were on horseback and the law stopped at the county line,” explains Kraus, likening their story to the outlaw tale portrayed in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. “But they quickly adapted to the use of fast cars and nitroglycerin, with the law looking more like The Untouchables than the local sheriff.”

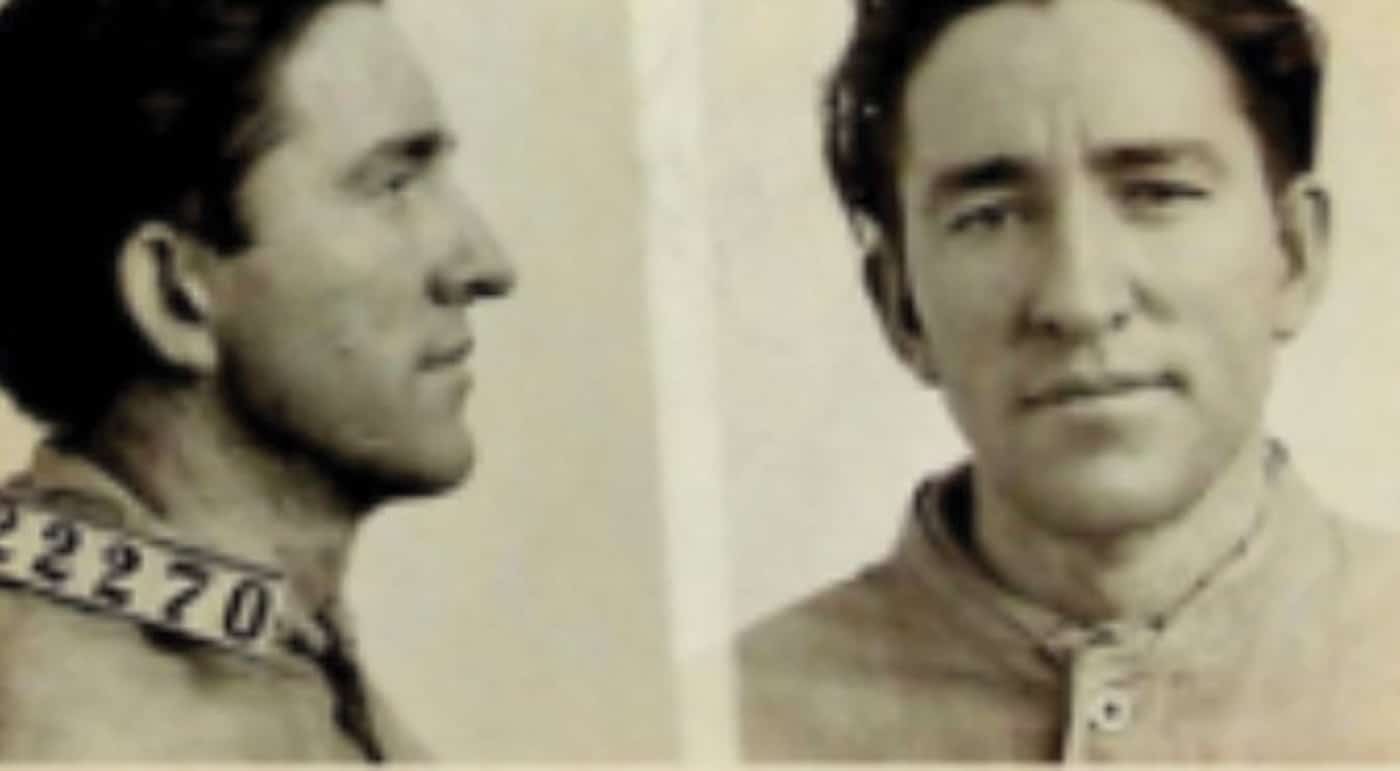

Another key factor in the Rondout robbery (and the thing that ultimately got the Newton Brothers a lighter sentence in exchange for their cooperation) was the involvement of Fahy, the corrupt federal employee who tipped off the mobsters about the train’s contents and when it would be rolling through Chicago.

“The Feds would not tolerate train robbery. Those who tried were quickly captured and thrown in prison,” says Kraus. “The schedules of the mail trains that carried significant amounts of cash were closely guarded secrets and the trains carried armed guards. The Newtons pulled it off because of an insider within the Postal Service. The gang knew what day, what train, which car, and how many bags contained the loot.”

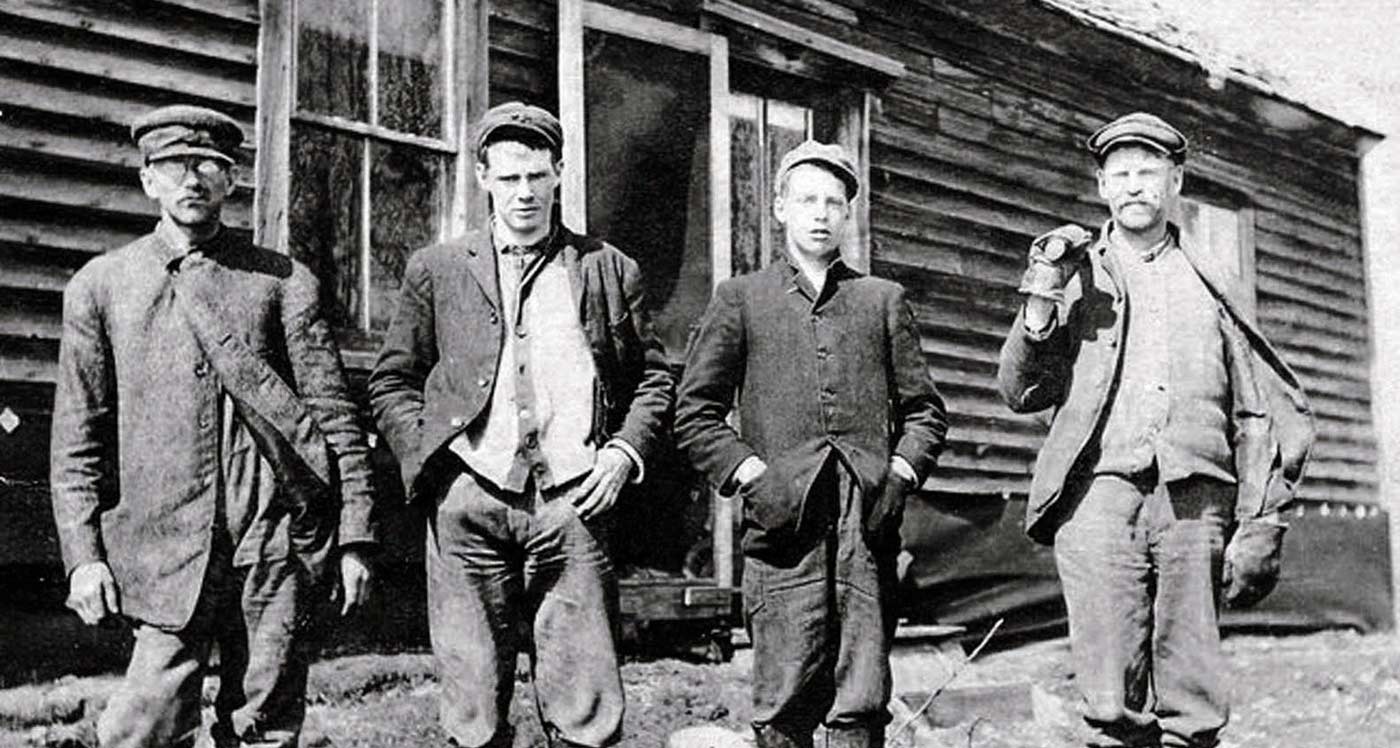

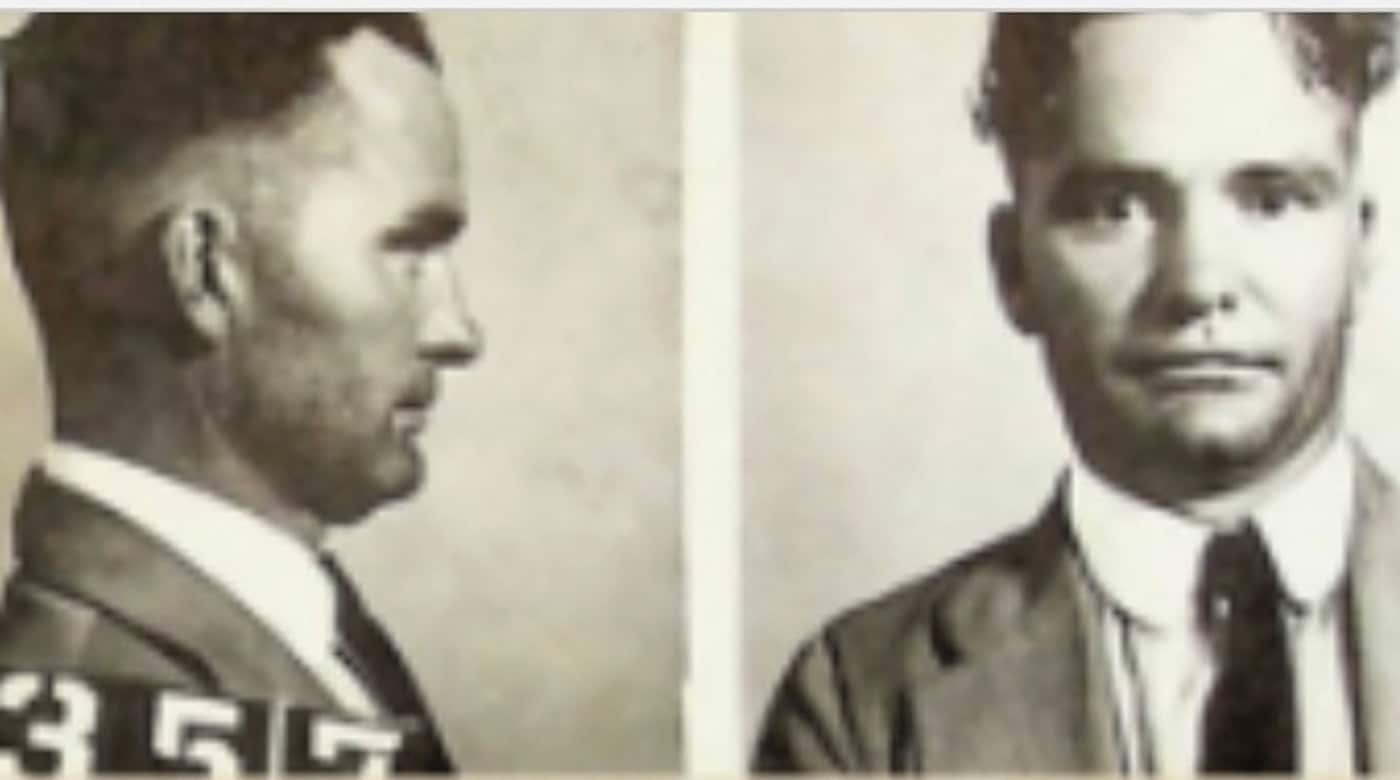

Growing up a in a family of 11 in rural Texas, Willis, Doc, Jess, and Joe Newton were already well known to the Texas Rangers for robbing banks and trains across multiple states and Canadian provinces.

“They kept under the radar by never hurting or killing anyone, rarely using guns, operating mostly at night, hitting rural or small towns, and not getting greedy,” Kraus adds. “In between jobs they lived respectable lives in big cities like St. Louis, Kansas City, and Chicago. They went to baseball games and events like the Kentucky Derby—until the money ran out.”

All but $200,000 of the more than $2 million stolen that day in Rondout was eventually recovered. As to what happened to the rest of the loot, no one knows for sure but it’s certainly a topic Kraus plans to address at the June 9 presentation.

Other topics include the transition from the agrarian economy of the Wild West to the urban, technology-driven culture of the Roaring Twenties and how families like the Newtons struggled to adapt to the changing times.

As for what happened to the Newton gang, history shows that Willis and Joe Newton stayed alive long enough to participate in David Middleton and Claude I. Stanush’s 1976 book, The Newton Boys: Portrait Of An Outlaw Gang—a tale that continues to captivate the imagination a century later.

Doors for “Distilling History: The Great Rondout Train Robbery” open at 3 p.m. next Sunday, June 9, with the presentation starting at 3:30 p.m. Advance reservation is highly recommended as previous Distilling History events have sold out. Tickets to the program are $30 and include a cocktail and light snacks. North Shore Distillery is located at 13990 Rockland Road in Libertyville. Purchase tickets online at lakebluffhistory. org/events. For more information, call 847-482-1571, email [email protected], or visit lakebluffhistory.org.

Sign Up for the JWC Media Email