CHICAGO: PREEMINENTLY PICASSO

By Jennifer A. Moran

Pablo Picasso

By Jennifer A. Moran

Pablo Picasso

A one hundred and thirty years since Pablo Picasso’s career as a painter is considered to have begun with his entry into Barcelona’s Escola Provincial de Belles Arts, the artist’s legacy remains a universal force. The late Richard Gray, legendary Chicago collector and one of this country’s foremost art dealers once wrote, “No one involved in any way with the visual arts can fail to be touched by his genius. Picasso’s work has been an ever-present influence.” Perhaps in no other American city is the artist’s pervasiveness felt more than in Chicago.

In 1913, the Art Institute of Chicago became the first museum in the United States to present Picasso’s work. The Arts Club of Chicago debuted his initial solo exhibition in the U.S. in 1923. In 1926, with its acquisition of The Old Guitarist (1903–1904) the Art Institute became the initial American museum to have Picasso’s work on continual display. The artist’s first monumental sculpture and his largest three-dimensional work, Chicago Picasso (1964–1967) in Daley Plaza, remains one of the city’s great icons. Picasso gifted the 50-foot-tall, 162-ton sculpture to Chicago, and it has continued to capture the imagination of the city and its global visitors ever since.

In a recent conversation, Jay A. Clarke, Rothman Family Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute, co-curator of the museum’s exhibition, Picasso: Drawing from Life, commented, “Picasso had a unique connection with Chicago.” While the Modern Master never came to America, Clarke notes that there was “something special about Chicago and Picasso. It’s rather intangible, but absolutely, there has always been a defining quality between this city and the artist.”

Discussing the origins of this mutual attraction, Clarke says, “There was what could be called a new Americanism here that probably fascinated Picasso. The city’s transformation [after the Great Chicago Fire], its cutting-edge architecture, its embrace of new forms, and its brashness, would have appealed to him. The sheer speed of the city, how rapidly it grew and rebuilt itself, was part of what may have also propelled Picasso’s interest.” Reflecting on Chicago Picasso, Clarke remarks, “Representatives from Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) personally visited Picasso. SOM’s Richard J. Daley Center (1965) is an architecturally significant building, and I think that was something he wanted to be affiliated with. It’s no coincidence that his sculpture stands outside of it.”

At the core of this nexus between Cubism’s creator and Chicago, are the city’s collectors. Clarke observes, “There has always been this sensibility about Chicago collectors. They are forward- thinking risk takers, astute, always pushing the envelope and collecting art of the moment. Absolutely extraordinary and singular in this country really.” Early quintessential Chicago collectors, Bertha Honoré Palmer, who began amassing Impressionist works, and Arthur Jerome Eddy, who pursued German Expressionism, were acquiring works considered avant-garde at the time.

Past Art Institute Director Charles Cunningham once noted, “In few cities in the world has Picasso’s work been collected as extensively as Chicago.” Clarke underscores, “Picasso was keenly aware of the city’s sophisticated art buyers. There are still new stories being uncovered about his interconnection with people in Chicago.” Among Picasso’s many Chicago-based followers were legendary civic leaders like Bobsy Goodspeed, an Arts Club president who was a good friend of Gertrude Stein and often visited Picasso; Margaret Day Blake, the Art Institute’s first female trustee who purchased his aggressive The Minotaur (1933) as a gift to the museum; Eleanore and Daniel Saidenberg, the artist’s American dealers, who began their careers at the Goodman Theatre and Chicago Symphony Orchestra respectively; and longtime Fifth Ward alderman and lawyer Leon Despres, a collector of Picasso etchings.

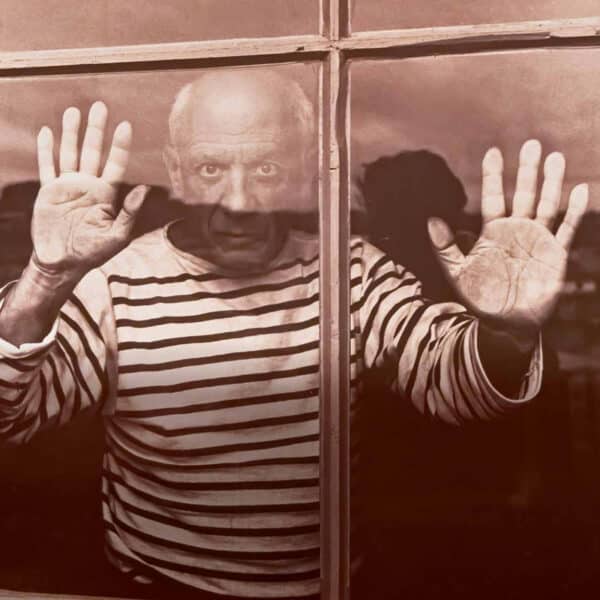

A part of this powerful narrative is the decades-long collaboration between Picasso and the renowned Swiss art dealer, Angela Rosengart, who founded the famed Rosengart Collection Museum. A neoclassical landmark in Lucerne, its permanent collection features more than 130 works by Picasso. Now 92, Rosengart first met Picasso when she was 17. Picasso created Rosengart’s portrait five times from 1954 until 1966. During a recent conversation, Rosengart recalled her experiences sitting for him. “It was very exciting. Picasso simply said, ‘Come tomorrow, I’ll do a portrait of you.’ When he worked, I felt as if he were peering into my soul. It wasn’t easy to bear his gaze. I wasn’t allowed to move or speak. After each session, I was exhausted. I must confess I didn’t sleep much the nights leading up to those moments! I was overwhelmed. I felt I had slipped into immortality.”

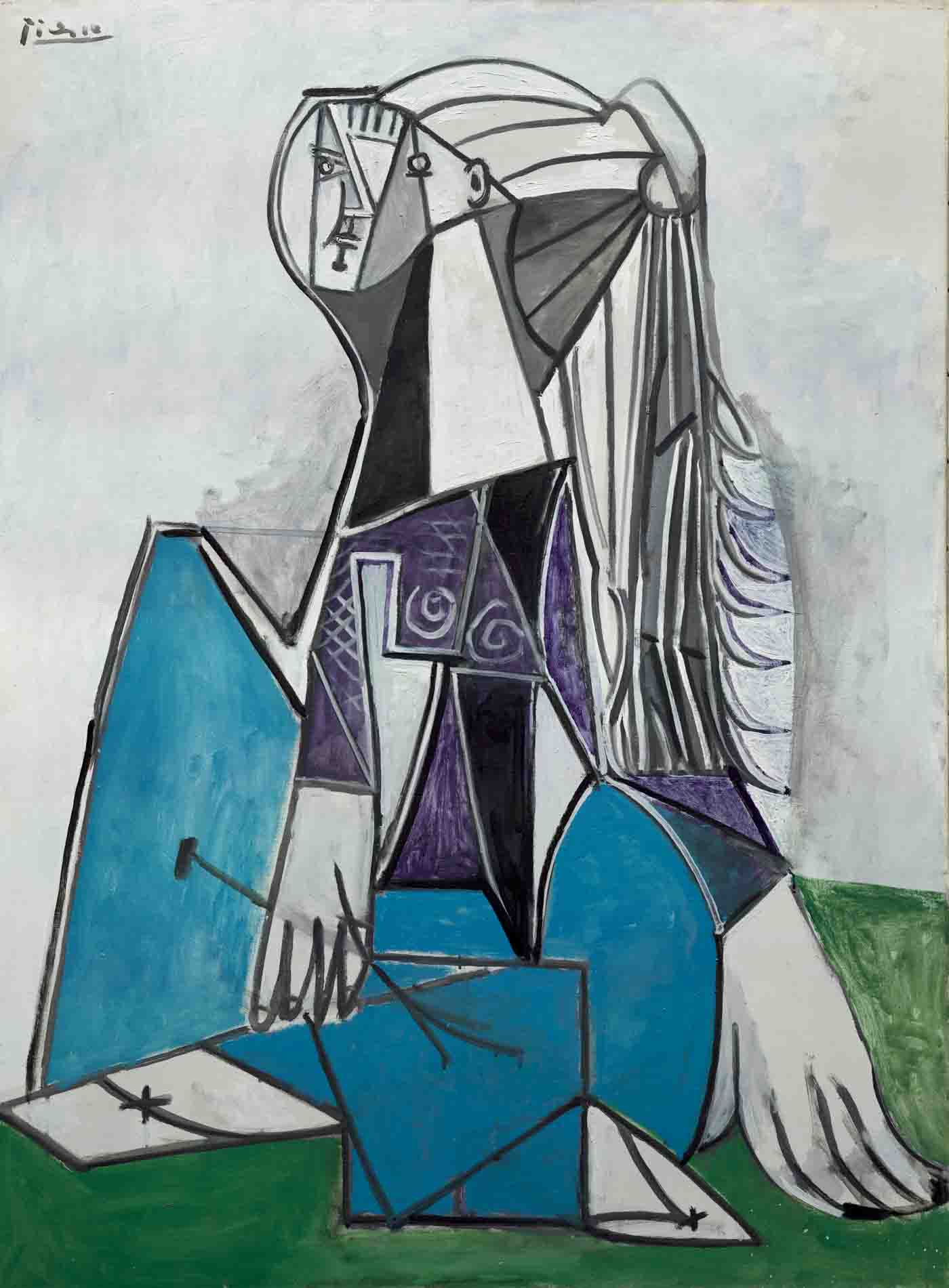

With her father, the gallerist Siegfried Rosengart, Angela sold Picasso’s Portrait of Sylvette David (1954) to Chicago philanthropists Mary and Leigh Block. The canvas, which now hangs in the Art Institute’s Modern Wing, illustrates French journalist Pierre Daix’s perception that “Picasso relied on his painting to prove that art is the strongest, much stronger than age or the tragedies of [an] era; that it can transform everything.”

Sign Up for the JWC Media Email