BELOW THE SURFACE

By Thomas Connors

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARIA PONCE

STYLING BY THERESA DEMARIA

HAIR & MAKEUP BY LEANNA ERNEST

Mairin Hartt wearing Proenza Schouler dress, Neiman Marcus Northbrook and Canned Goods cuff, cannedgoods.com

By Thomas Connors

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARIA PONCE

STYLING BY THERESA DEMARIA

HAIR & MAKEUP BY LEANNA ERNEST

Mairin Hartt wearing Proenza Schouler dress, Neiman Marcus Northbrook and Canned Goods cuff, cannedgoods.com

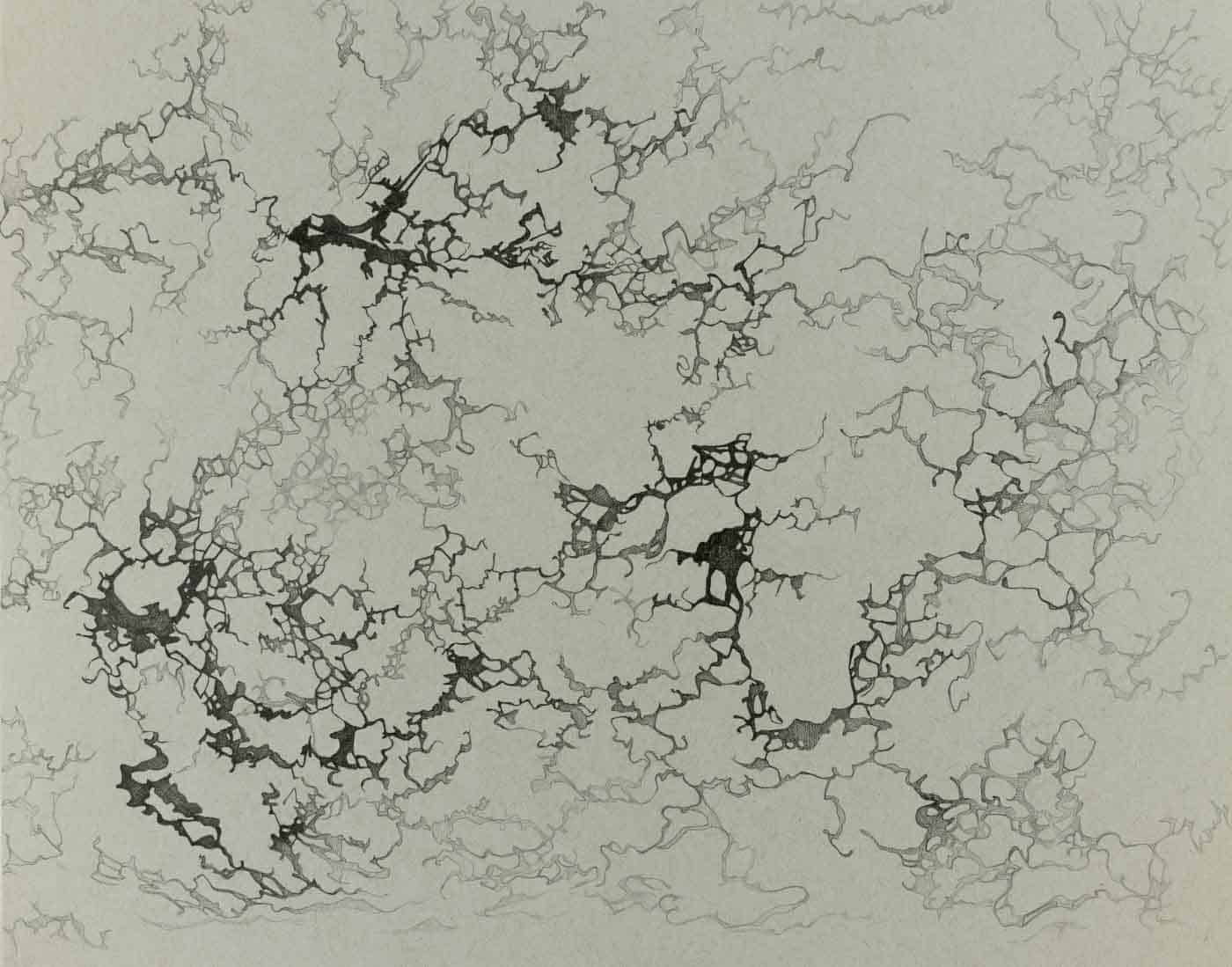

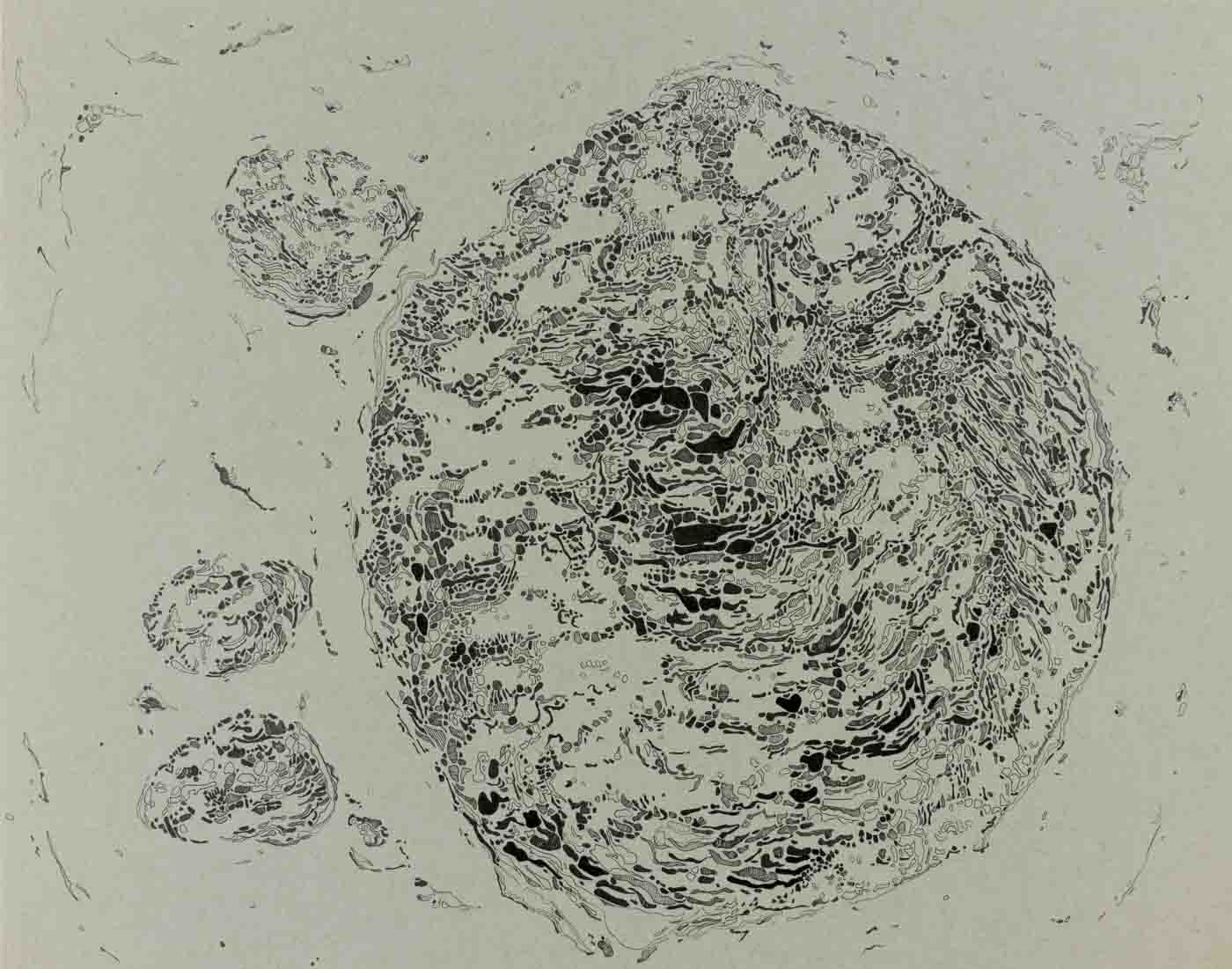

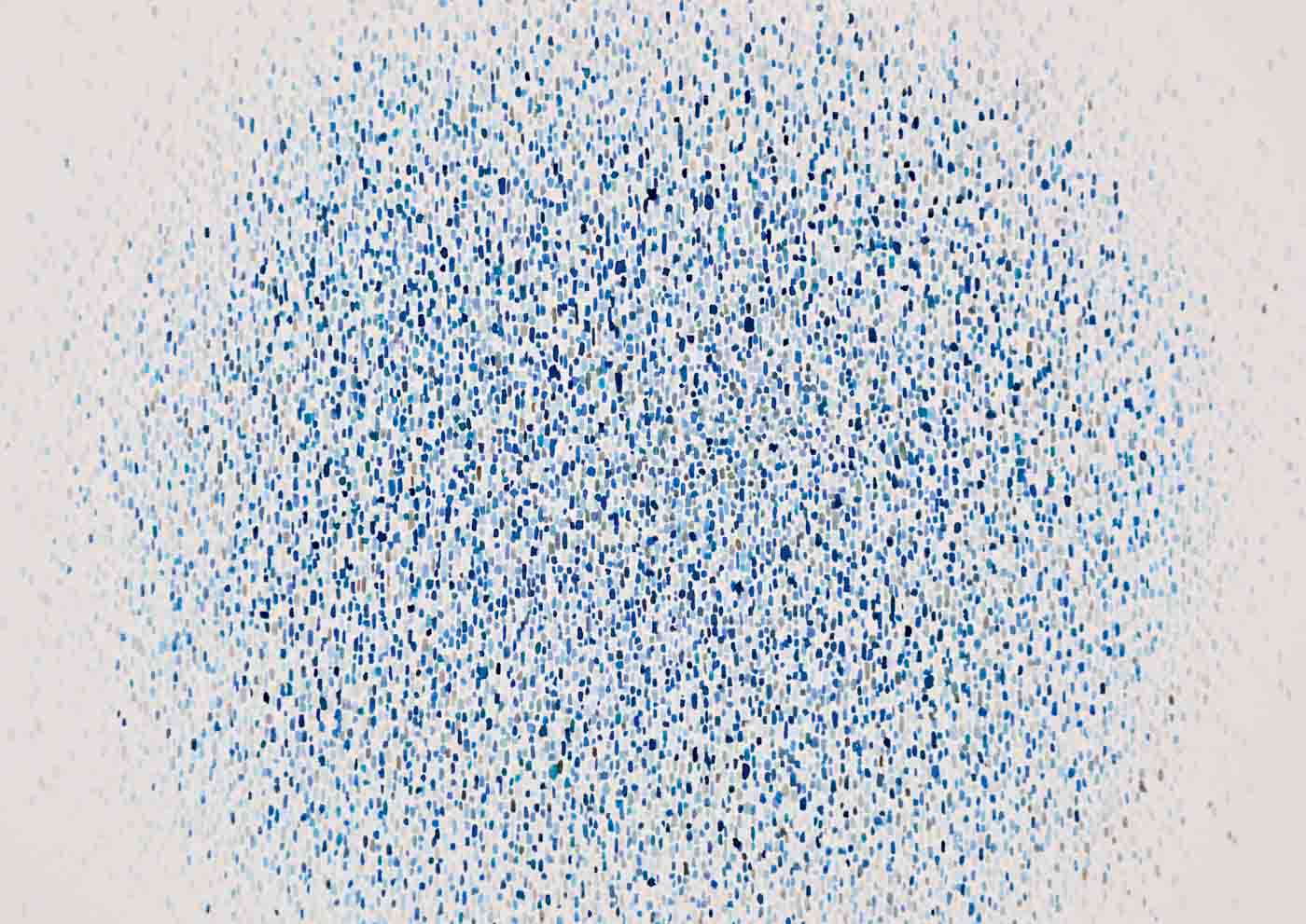

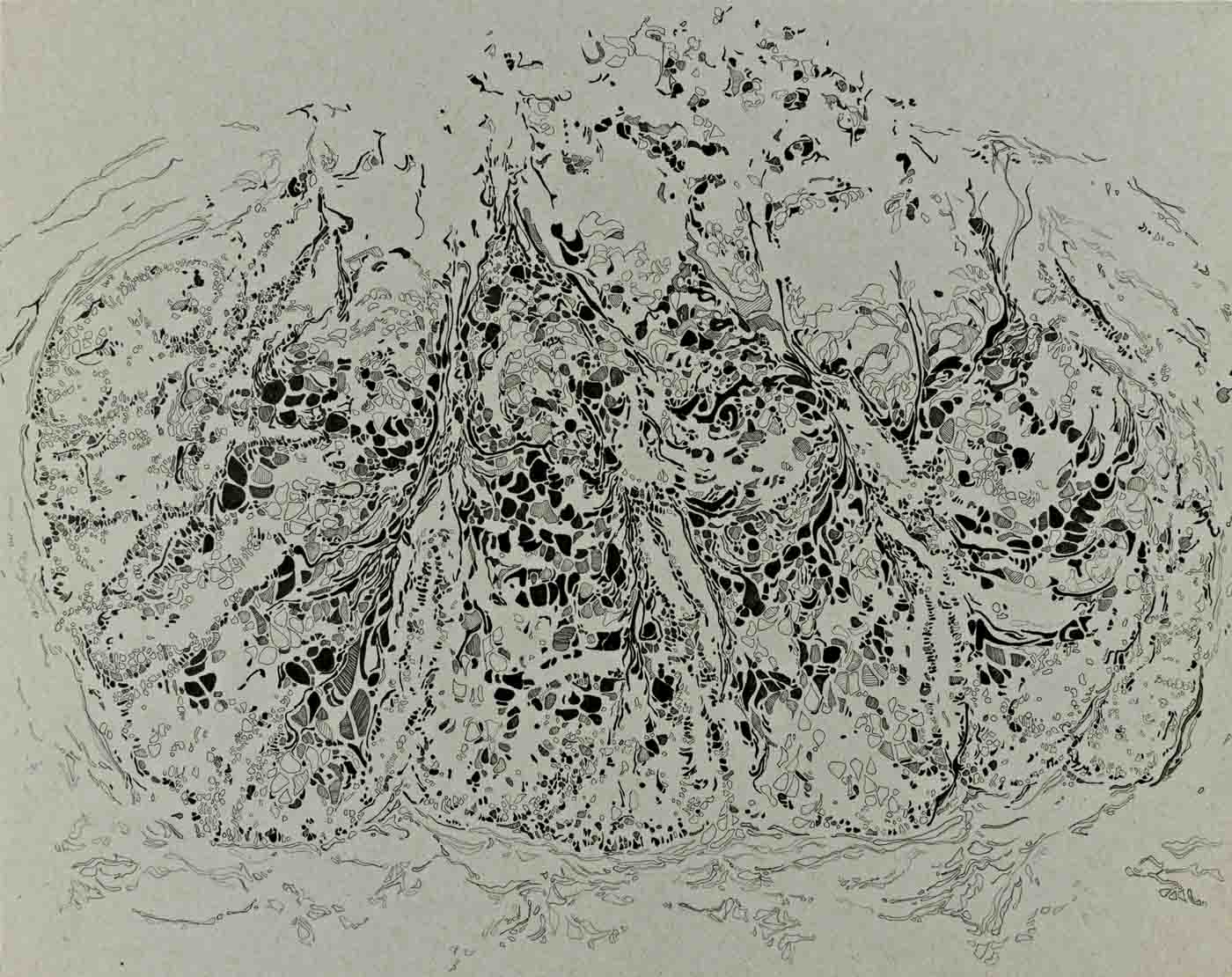

The imagery of artist Mairin Hartt occupies a zone between the solid and the immaterial. Hinting at both disorienting randomness and inscrutable organization, it registers as remnants of what was and intimations of what may come to be. “My work,” she has written, “is an attempt to establish a physical representation of the elusive—exploring the uncomfortable space between growth and decay, existence and non-existence.”

A lifelong Chicagoan, Hartt has been drawing since she was a kid. “As a child, my goal was to get better at representation—I wanted what I drew to look more like what I saw in real life. I drew everything, especially portraits of my siblings since they were the few willing to indulge me. In high school, my work veered more into Expressionism, using lots of color to ‘grab the viewer’s attention.’ Initially, I thought I’d be a portrait painter, but eventually, I asked myself why I was creating portraits and realized that it was because of all the wonderful shapes that made up the human face, rather than the face itself.”

A milestone in Hartt’s creative evolution, her journey through form and content, technique and expression, came in her junior year at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. “I was trying to figure out what my work was about, how my interest in science, art, and nature came together,” she recalls. “I was sitting in my art history class, listening to a lecture on the Romanticists and the Sublime, in which the viewer was instilled with feelings of awe, fear, and a sense of the infinite, leading to one’s sense of mortality. This felt like something I had been trying to do in one way or another. It made me think of times in my life when I might have felt the sublime—hearing my heartbeat at the doctor’s office at age 6, being completely mesmerized seeing Monet’s haystacks for the first time or looking through a microscope at impossibly small cells and organisms, an entire universe we can’t see.”

Furthering Hartt’s interest in disorder and dissolution was an Environmental Science and Policy class. “We were discussing energy and the second law of thermodynamics, which, in very simple terms, means that entropy increases over time. My professor made an offhand comment, that considering the principle of least effort—organisms wanting to use the least amount of energy for the greatest gain—life should not exist. That statement took me aback and after class, I asked him, ‘How does life exist, then?’ And he responded, ‘Well, that’s the question.’”

Hartt, who is Director of Education at The Art Center Highland Park, went on to earn a Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. While there, she explored the idea of the sublime—that momentary sense of wonder that makes us stop and think—on a small scale, applying ink to glass slides that she then installed in boxes and lit from behind. With their visual field reduced when they peered inside, viewers were caught in an experience both restrictive and expansive. Since then, Hartt has been rigorous in her explorations. Against the grain, a series of mixed media drawings, referenced microscopic cross-sections of human tissue. With Non-Existent Decay, she traced eroded chunks of concrete onto Mylar and added her own marks in graphite and ink to allude “to both celestial bodies and microscopic entities, reflecting the interconnected complexities between entropy and existence.”

Clearly, Hartt isn’t interested in making purely pretty pictures. “My more abstract pieces tend to get a wide range of reactions, becoming an object for projection that reveals more about the viewer than the artwork,” she observes. “I was in a group show in 2015 called Lexicon in which artist statements were not displayed, so viewers could guess what the artwork was about and write down their reactions on sticky notes placed next to the artwork. I was exhibiting a piece from my Repetitious Infinitum series, and most of the responses said it reminded them of a heartbeat or lines from a seismograph, which I thought was interesting since the line work in that piece was copied from cracks in a concrete floor.”

Hypnotic and perhaps hard to read, elusive yet illustrative, Hartt’s work is as mysterious as life itself.

For more information, visit mairinhartt.com.

Sign Up for the JWC Media Email