Allusionism

By Monica Kass Rogers

By Monica Kass Rogers

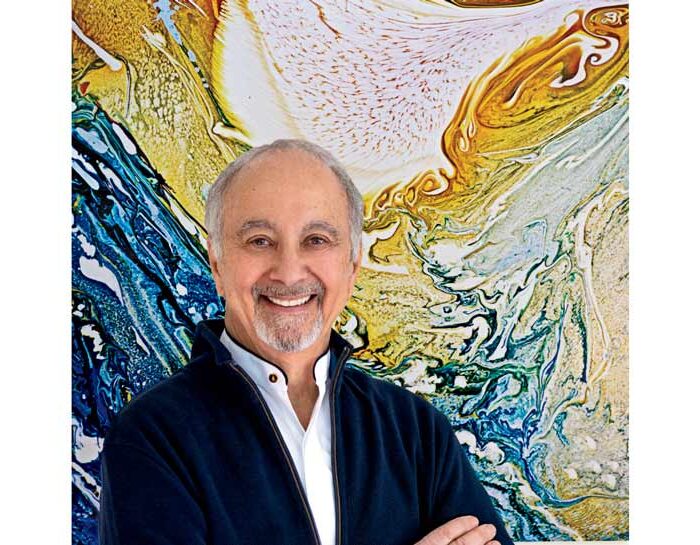

Swirling among blooms of creative thought in the imaginative world of inventors, the question, “What if I did this?” has prompted more discovery and ingenious solutions than any other. That’s certainly been true for Jerome Caruso, Lake Forest-based inventor, designer, and creator of a new art form he’s dubbed Allusionism.

In his lifetime, Caruso’s inventions and designs have resulted in more than 100 U.S. and international patents. He’s perhaps best known for the invention of “invisible refrigeration” for SubZero, and, for designing the look of Wolf cooking ranges, integrating both into the seamless paneled “Evolution System” that revolutionized the look of modern home kitchens today. And then there is his furniture design work. That includes everything from the Bi-Cast chair—the first, completely machine-produced stacking chair, (included in the permanent American Arts Collection at the Art Institute of Chicago,) to his award-winning ergonomic Celle chair for Herman Miller.

As he did with those revolutionary designs, Caruso’s new Allusionism art form blends art, science, and technology.

“Over the past five decades,” says Caruso, “my interest in a physics approach to design led to inventions and breakthrough consumer products for international companies. But I’ve always also been interested in pure art. And so, I followed this same physics-based approach in my quest to create transformative art.”

“Over the past five decades,” says Caruso, “my interest in a physics approach to design led to inventions and breakthrough consumer products for international companies. But I’ve always also been interested in pure art. And so, I followed this same physics-based approach in my quest to create transformative art.”

Decades ago, Caruso started experimenting with unique ways of painting. Eventually, he developed a process that creates an evolution of forms and colors that are not visible to the human eye without magnification. Using hiresolution digital technology, Caruso magnifies his paintings, creating abstract artworks that can be scaled to wall-sized dimensions for dramatic effect.

The artworks are brilliant, swirling, expressive landscapes of color that range in emotive content from peaceful and soothing to passionate and fiery.

“My intent,” says Caruso, “was to use color and detail to create a world of imagination and meaning open to individual interpretation. The art often alludes to nature, evoking memories and experiences that can be very personal.”

The Allusionism process (patent pending) begins with a small original painting Caruso calls a “cell.” To make each cell, Caruso visualizes a composition and works with a limited palette of reds, blues, and greens.

“I paint with liquid colors that are always in a fluid state on a small panel,” he explains. “The paints are formulated to encourage microscopic action. As the paints flow and move, they chemically blend into secondary and tertiary hues, producing an evolution of colors and shapes. This process creates some effects that I can anticipate and influence with my brush and timing during the various stages of drying. Other effects are surprises that take the art in new directions I’m excited to pursue.”

Once the colors are no longer liquid and the painting dries, the cell is complete and ready to be magnified with high-resolution digital photography. With magnification, barely-perceptible shapes and color variations in the original cell become apparent.

“Imagine looking at a flower petal or butterfly wing under a microscope,” says Caruso. “It’s a bit like that.”

Finished works are printed as large-scale giclées, that are then mounted and sealed with a polymer coating, sized according to the display space.

But in the first public display of an Allusionism work, a Caruso painting, titled, Dawn has been translated into seven, 14-foot-tall, stained-glass windows newly installed at Northwestern Medicine Lake Forest Hospital’s chapel.

For this installation, the tall, round profile of the chapel needed to be taken into consideration. For best effect, the painting was divided into seven sections, balanced to achieve a one-vista dynamic. These were then created into interior art-glass panels by the renowned stained-glass studio Franz Meyer, of Munich, Germany. The studio used a special technique of applying ceramic frit (silica and fluxes fused at high temperatures to make colored glass) to each panel. This resulted in perfect, glass representations of the fine details in Caruso’s painting, without the distraction of metal fretwork divisions commonly seen in the stained glass windows of churches and cathedrals.

Also revolutionary, Caruso conceptualized a special lighting system to illuminate the panels throughout the day and night, which adjusts to ambient, exterior light levels. To accomplish this, Caruso placed a light source at the top of each panel, between the external, insulated panes and the art glass. LED components were chosen to create a graduated light level— brighter at the top, and diminishing downward.

The resulting effect is both contemplative and uplifting.

“It has been especially gratifying that the first public installation of a work of Allusionism is in this setting,” says Caruso. “A hospital is a unique theater with high drama and the full range of human emotions expressed daily. And the chapel in such an institution, even more so. The installation of Dawn here, brings with it the hope that people will enter into the chapel and envision the bright possibilities of a new day.”

Sign Up for the JWC Media Email