A SHAPE TO FILL A LACK

By Thomas Connors

PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF CHILLIDA LEKU

Chillida Leku

By Thomas Connors

PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF CHILLIDA LEKU

Chillida Leku

There was a time when it was practically a rite of passage for young artists to make a pilgrimage to Paris. Many stayed. Others descended on the city, imbibed the “ism” of the day, and moved on. In 1948, Eduardo Chillida, a native of San Sebastián, Spain, began a four-year sojourn in France. An architecture student who had switched his focus to art, he was taken with the ancient Greek sculptures in the Louvre and began making figurative forms in plaster. Three years later, now married, he was back in the Basque country, living in the village of Hernani. It was here, one could argue, that his true life as an artist began when he walked into the local blacksmith’s shop and began to work with iron. In 1958, Chillida won the grand prize for sculpture at the Venice Biennale and came to Chicago on a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in Fine Arts. In time, the Art Institute of Chicago acquired several of his works, most notably Abesti Gogora III, a monumental piece in oak.

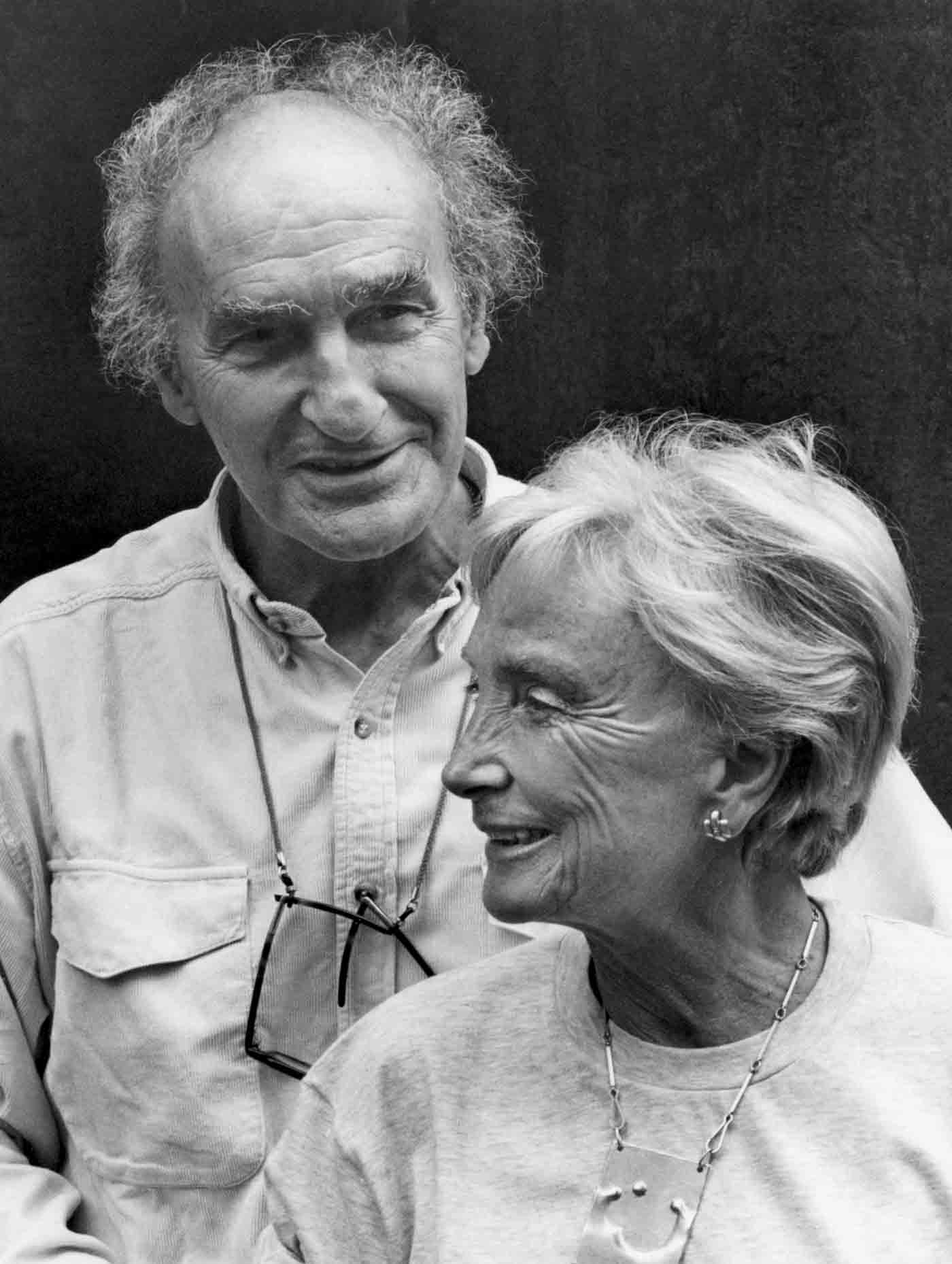

2024 marks the 100th anniversary of Chillida’s birth, and, although his work can be seen in many cities and institutions here and abroad, it’s quite something to experience it at Chillida Leku, the sculpture park and exhibition space he founded outside Hernani, just a few miles from San Sebastián. Chillida and his wife, Pilar, purchased the property in the 1980s and spent 15 years composing the landscape (with an assist from Piet Oudolf, who collaborated on New York’s High Line) and transforming— with Basque architect, Joaquín Montero—a rustic, 16th-century country house into a gallery space. More than 40 of the artist’s works—from smaller alabaster pieces to towers of iron—are displayed indoors and out across the 40-acre property.

Where the work of Alexander Calder strikes one as constructed and Henry Moore’s sculpture seems molded, the art of Chillida reads as if drawn, even excavated. And in fact, the notion of interiority, of space within a sculpture, was a key concern of the artist. As he said, “A room with the door closed is different from the same room with the door open,” and certain of his pieces are as intriguing for the way they occupy space as for the way they close space off, burying it within his sculpted forms. While this abstraction might suggest his work speaks only to the egghead art expert, nothing could be further from the truth. Chillida was a great reader, a man keen on philosophy but an individual who was at home with bafflement. “I believe I should try to do what I don’t know how to do, to try to see where I can’t see, recognize what I don’t know, identify with the unknown.”

“My grandfather,” shares Mikel Chillida, “always said that if somebody asked for an explanation of his work, he would take them to a tree and ask, ‘So, you like this tree? Yes? Explain the tree to me.’ It was the same with his sculpture. Of course, the more knowledge you have, the deeper you can go, but the main thing is, does it move you or not? It’s that simple.”

Indeed, it is difficult not to be moved when encountering Chillida’s work. Not merely moved emotionally but also with a certain wonder at these unique shapes, at the way they touch the ground or distance themselves from it, at the play of solid and void, at the way the natural materials are transformed into unnatural geometries and yet retain their elemental power as the stuff of the earth. Firm and seemingly unassailable, sometimes cryptic and challenging, they possess a kind of self-possession, operating beyond the hand of the artist, existing in the world on terms that perhaps he never imagined. As Chillida said himself, “All my work originates in questions. I am a specialist in questions—some without answers.”

For more information, visit eduardochillida.com/en/chillida-leku.

Sign Up for the JWC Media Email